By: David C. Weinczok

“Treacherous and vile wolves”. That’s how Walter Bower, writing on the island haven of Inchcolm in the Firth of Forth in the 1440s, described the Scottish nobility. In contrast, the crown – at the time worn by James I – was a bulwark against the self-interested, anarchic nobility. If any noble got too high and mighty, the king would lay siege to their castle, pry them out of their stone shells, put them in their place, and peace would return to the land. The knives were always out, and pointed in all directions.

At least, that is the version of late medieval Scottish history that many students have been taught to accept. It’s a top-down view, one in which the institution of the crown is the ultimate, and rightful, authority. In most conventional historical narratives, the crown is always presented as a force for stability, and the nobles always a force for ambition and chaos who need to be tamed like wild beasts.

Primitive state

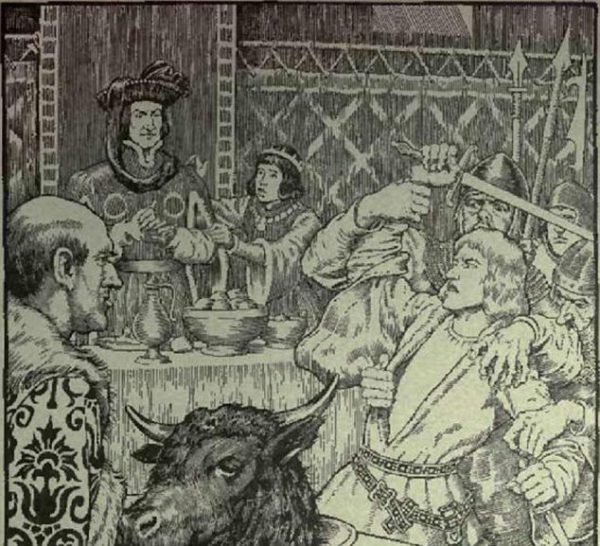

It’s an enduring narrative, and there are numerous incidents that seem to support it. The alleged treason and subsequent execution of Murdoch, Earl of Albany, in 1425. The infamous ‘Black Dinner’ of 1440 resulting in the murder of the Earl of Douglas at Edinburgh Castle, and the murder by the king’s own hand of another Douglas Earl suspected of treachery at Stirling in 1452. The rebellion of the Darnley Stewarts in Renfrewshire in 1489, which required the king’s army to come calling with a royal artillery train in tow. James IV’s unsuccessful siege against Archibald ‘Bell the Cat’ Douglas at Tantallon Castle in 1491. On and on the list goes, full of examples of revenge, treachery, jealousy, violence and the rebalancing of power in favour of whoever sat on the throne.

It may surprise you, then, to learn that between 1341 and 1469 there were twice as many rebellions and three times as many civil war battles in England than there were in Scotland. Three times as many English magnates were killed for political reasons than their Scottish counterparts (even though the magnate class in each country was comparable in size). Looking further afield, we find that political violence in late medieval Scotland was no more rife, and in some cases markedly less so, than in other European kingdoms. So, why do we still think of that period, in Scotland specifically, as an especially venomous viper pit?

Many historians, especially during the mid-20th century when disciplines like castle studies flourished, were stuck on the idea that Scotland was an irredeemably warlike nation. This is partly due to the firmly pro-Union politics of the era, in which the unquestioned orthodoxy was that the Union of the Crowns in 1603 and the Act of Union of 1707 had a ‘civilising effect’ on Scotland. This was accompanied by fervent support for the modern monarchy. From this perspective, the alleged anarchy of medieval Scotland was a natural consequence of its more ‘primitive’ state, one that was tamed by a unified central authority based in London rather than Stirling or Edinburgh.

Another factor was that many of the most prominent historians of the mid-20th century had experienced first-hand the terror of one, if not two, world wars. Understandably, those experiences deeply shaped their perspectives and convinced them that Britain was a place constantly under siege by enemies outwith and within its borders. This trickled down in interesting ways, such as the now-rejected concept of ‘bastard feudalism’. This was the idea that medieval lords in their castles lived in constant fear of their soldiers and mercenaries rebelling. As a result, they designed their residences to keep their fickle retainers separate from themselves and their families.

Relationship between the nobility and the crown

As ever when studying history, taking into account the biases and perspectives of the historians who write it is just as important as understanding the events themselves. Not just modern historians, either. When Walter Bower deemed the nobility “vile wolves” in the 1440s, he knew it would go down well with his intended audience: the king. Along with the epic poem The Brus written by John Barbour in the late 14th century, Bower’s Scotichronicon was part of a suite of ‘royal propaganda’ intended to legitimise the Stewart dynasty’s right to rule. While Scotichronicon did levy some critiques against king James I, it nonetheless presented the crown as the ultimate source of legitimacy and authority. When historians in the late 19th and 20th centuries read these medieval sources they found a worldview sympathetic to their own, leading many to adopt it uncritically.

More recent research by scholars such as Katie Stevenson, Jennifer M. Brown and Alexander Grant emphasises a more complex relationship between the nobility and the crown. For example, Hugh Montgomerie, a late 15th century Ayrshire nobleman, was able to act with extraordinary impunity: he had the leaders of two rival families, the Boyds and Crawfords, assassinated, and utterly destroyed the Cunningham stronghold of Turnielaw. By any definition this was a disruption of the peace and a power grab by Montgomerie. Yet because he took the side of the future king James IV at the Battle of Sauchieburn, that king was content to forgive these transgressions. A noble’s ambition, it seems, was not a bad thing in itself. So long as you show up the for crown when it counted, the iron fist of the king’s justice would land somewhere else.

This vision of a more symbiotic relationship between nobles and the king is just one way that the narrative of a uniquely violent and adversarial medieval Scotland is being deconstructed in recent decades. Whenever we are presented with theories for how a society worked (past or present), it is a good idea to bear in mind the adage of the late Canadian political theorist, Robert Cox: “theory is always for someone and for some purpose”.

The more blood-drenched image of Scotland made sense to an overwhelmingly pro-Union generation of historians scarred by the horrors of industrial warfare. The more nuanced reality may not be as salacious a story as one in which nobles and kings constantly vied for power in a zero-sum game, but I believe it hits closer to the mark of truth. And that, ultimately, is what good faith historical revisionism is all about.

Main photo: Tantallon Castle. Photo: David C. Weinczok.