Kinloch Castle on the isle of Rum is an ornate castle which was built by George Bullough, son of a rich industrialist and friend of the Japanese emperor in the 19th century. It was once a place where the fashionable set of the day including aristocrats and actors would visit. Now frozen in time but slowly crumbling despite all sorts of plans over the years, including intervention by the then Prince Charles, the castle is looking for help to secure its future as a key part of the small island community as Judy Vickers explains.

In fairy tales when a knight in shining armour arrives at a castle for a rescue, it’s generally a princess locked up inside who needs his assistance. In real life, however, on the Hebridean island of Rum, it’s the castle itself which needs help – and the knight in shining armour isn’t being welcomed by everyone.

The castle in question is next to the island’s tiny village of Kinloch. It is a pink-stoned turn-of-the-century crumbling pile owned by NatureScot, Scotland’s government-owned nature agency which has been trying to find a buyer and secure a viable future for it for years. The knight is multi-millionaire businessman Jeremy Hosking, who is said to be willing to buy it, stump up the millions to restore it and put it into a trust in order to open it to the public.

The news of Mr Hosking’s involvement earlier this year was welcomed by politicians, heritage experts and the campaign group Friends of Kinloch Castle. But some of those living in Kinloch aren’t so keen on the prospective new owner and have convinced a government minister to put a hold on the sale.

It’s just the latest twist in the tale of the castle which was once a playground for the rich with Gaiety Girls allegedly dancing on the grand piano and hummingbirds filling the conservatory but which is now more of a castle under a spell, its opulent Edwardian interiors frozen in time, waiting for a knight with deep pockets to stop their slow decay.

The most ostentatious shooting lodge ever

Kinloch is now the only inhabited settlement on the island of Rum (sometimes written Rhum or Rùm). The diamond-shaped island is one of the four main Small Isles of the Inner Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland. The others are Eigg, famous for its community buyout 25 years ago; Canna, owned by the National Trust for Scotland; and Muck, privately owned by the MacLean family – Lawrence MacLean, who died in May, was known as the Prince of Muck. Rum has always been at the whim of its wealthy owners. When the kelp industry – used to make soda ash for explosives – dried up after the Napoleonic Wars, the island was given over to sheep farming and within less than 40 years a population of more than 400 had been cleared by the owners, the Macleans.

It was then owned by a succession of wealthy landowners, when it became known as the Forbidden Island as uninvited island visitors were discouraged – there was no ferry service in those days. In 1884, John Bullough, a mill owner from Lancashire in England, became the latest of those rich landlords. He bought the castle to create a shooting pleasure park, introducing deer and game birds, and when his son George inherited it in 1891 he built perhaps the most ostentatious shooting lodge ever – Kinloch Castle.

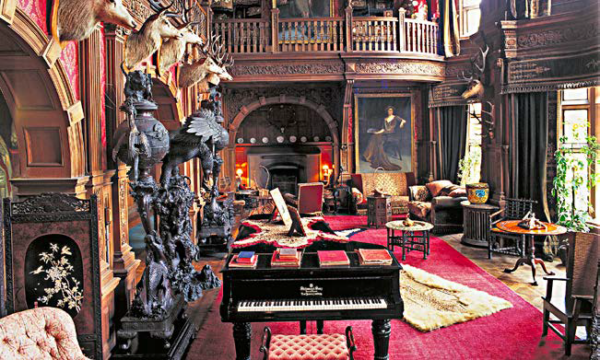

The castle took three years to build, from 1897 to 1900, with pink sandstone imported from the island of Arran and 250,000 tons of soil for the gardens. It was state-of-the-Edwardian-art with a hydro-electric scheme, one of the first at a private residence in Scotland, allowing electric lights and air conditioning – there was also double glazing and an inter-room telephone system, as well as a lavish interior décor with mahogany panelling, stags’ heads, tiger skins and Eastern exotic treasures, many gifts from the Emperor of Japan, whom George had struck up a friendship with while sailing the world on his 221-ft yacht the Rhouma.

A special German-built orchestrion, an elaborate electric pipe organ designed to simulate the sound of an entire orchestra, had originally been ordered by Queen Victoria, destined for Balmoral Castle, but her death saw it diverted to join the other extravagances at Kinloch. Outside, a domed glasshouse – which later blew down in a storm – was full of hummingbirds, turtles and alligators (the latter in heated tanks), while the walled garden was lined with hothouses containing peach and fig trees. While the scratches on the grand piano were actually made when a brass incense burner was knocked over rather than the heels of dancing London chorus girls, the castle’s heyday did see parties full of bright young things fill the ballroom, billiard room, galleried hall, dining room, drawing room, morning room, squash court, bowling green or small golf course – and of course out on the hills shooting for the fashionable “Highland season”.

Opulent grandeur has been quietly decaying

It was a brief moment in the sun, however. There was little time, money or manpower for such frivolities in the aftermath of the First World War. George – Sir George from 1901 when he was knighted for turning his beloved yacht into a hospital ship during the Second Boer War – died in 1939. His widow, Lady Monica Bullough, sold the island to the Nature Conservancy Council, a forerunner of NatureScot, in 1957 “to be used as a nature reserve in perpetuity and Kinloch Castle maintained as far as may be practical” and Rum became a National Nature Reserve the same year. Only the family’s mausoleum remains in their ownership.

The island’s natural assets have since thrived – sheep and cattle were taken off the island and the natural woodland scrub allowed to return. The island’s famous red deer now form part of an internationally important study and eagles, both white-tailed and golden, as well as otters, dolphins and basking sharks are among the wildlife frequently spotted on land, sea and air. The introduction of the Small Isles ferry in 2004, complete with a new pier on Rum at Kinloch, means the once forbidden isle is now popular with tourists keen to hillwalk the Rum Cuillin, wildlife spot or enjoy its quiet beaches.

Even the population, which dwindled from 100 in 1900 to 28 in 1951 and remained at just over 20 for many years, has seen an increase in recent years. The Isle of Rum Community Trust has seen some of village transferred to community ownership and has built new homes, successfully attracting new families in 2020 and boosting the population to around 40.

But the last half a century has not been so kind to the castle and, despite some restoration by NatureScot, its opulent grandeur has been quietly decaying. The servants’ quarters were used as a hostel up until 2015 but now even that is closed and leaks, with dry rot and woodworm having taken hold. The castle’s appearance on the 2003 TV programme Restoration highlighted its plight and there were various schemes proposed including one from The Prince of Wales’s Regeneration Trust. But all have come to nothing so far. NatureScot has warned the public purse cannot afford its upkeep and a solution must be found soon. So will Mr Hosking, a noted railway enthusiast who has funded many steam heritage projects, be the saviour this sleeping beauty castle has been searching for, with the islanders’ fears over access roads and energy supplies overcome? Only time will tell.