By: Judy Vickers

As a sport, its fortunes have often reflected the ups and downs of life in the Highlands where it is played, from Celtic myths, through the Scottish diaspora and the decimation of young men during World War One to the challenges of modern rural life. And those with a passion for shinty – camanachd or iomain in Gaelic – will be hoping that particular tradition continues as the stick and ball sport looks to a future with more young people and women playing, and stronger ties to the Gaelic language, the native tongue in many of the areas where it still flourishes. This month the game’s 2023/24 season gets going, with 53 teams across six men’s divisions and 25 women’s teams playing for glory and the chance to win one of several trophies, the most prestigious of which is the Camanachd Cup with its final played in September.

A community-based game

Thousands across the Highlands, from islands such as Skye, and the west in Argyll up to Badenoch, where the mighty shinty clubs of Kingussie and Newtonmore rule, are involved in the game. Yet the sport takes a back seat compared to football or rugby in terms of headlines, even in Scotland. Camanachd president Steven MacKenzie says that it’s probably down to the fact the sport is still a community-based game. “We are pretty much a village sport, they are generally small communities playing, but it is a big deal within the Highlands.” As it’s an amateur sport, talented players don’t disappear off to the big cities with juicy sporting contracts, so in many ways shinty is still the sport it has been for centuries with community pitted against community for honour and pride.

In fact, shinty’s origins are lost in the mists of time. “We go right back to Celtic mythology,” says Steven, referring to an ancient legend about the game from Ireland. Shinty has common roots with the Irish sport of hurling – the sport was brought over by Irish settlers to Scotland centuries ago and while the sports have developed differently over the years they have enough in common for shinty and hurling teams to play each with adapted rules in international games. And the Irish warrior hero and demi-god Cú Chulainn gained his name thanks to the sport. According to Irish mythology, he was known as Sétanta until the day Conchobar, the king of Ulster, saw the young boy playing hurling and was so impressed he invited him to a later feast. Unfortunately, by the time Sétanta finished his game and arrived for the feast, the host Culann has loosed his enormous guard dog, which promptly attacked the approaching Sétanta. To save himself, he hit a mighty shot with his hurling stick and drove his hurling ball down the creature’s throat, killing it. As Culann is upset at the loss of his dog, Sétanta promises to stand in as his replacement guard until he can raise a new guard dog. And after that, during all his adventures, he is known as Cú Chulainn, meaning Culann’s hound.

While there probably weren’t many mythological giant hounds to deal with, shinty could be quite a ferocious affair in times gone by, with no strict rules on the number of players – it’s now 12 a side for the men’s game and ten for the women’s. Matches were village against local village, often on a holiday or feast day – New Year was a particular focus. Rules began to be made more uniform once the Camanachd Association, the governing body for the sport, was created in 1893 but a match could still be quite a lively affair, as Dr Isabel Frances Grant, the founder of the Highland Folk Museum in 1935, now located in Newtonmore, reported as she gathered anecdotes about Highland life. “To watch shinty at its liveliest one must see a match between the teams from two neighbouring and rival districts. The speed is terrific. The spectators, all local people, are whipped up to vociferous animosity against the opposing side. Casualties are borne off the field (sometimes including spectators hit when the ball flies wide) but they generally soon rise to re-engage in the conflict. After a cup-match the winning team carries the trophy home in triumph, and it is filled and refilled with whisky by a public-spirited hotel keeper and carried up and down the village street every passer-by being given a sip out of it.”

Helps to bind communities together

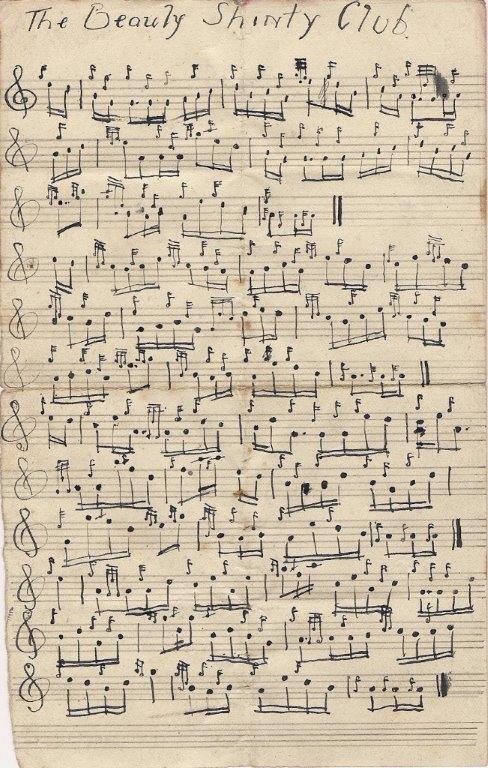

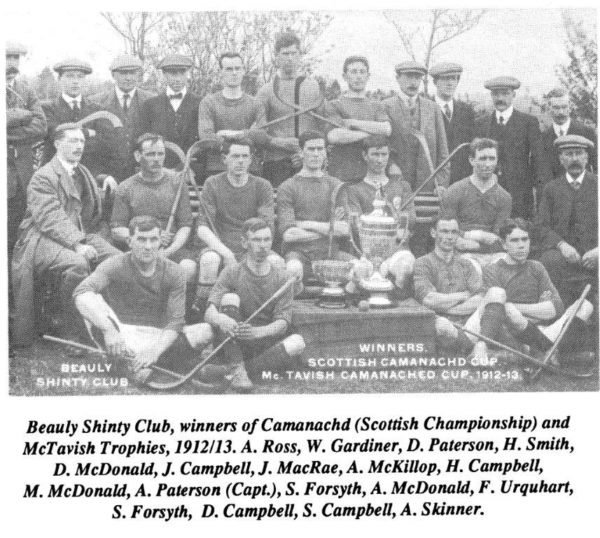

But the early 20th century also brought tragedy. Many Highland and island communities saw their populations of young men wiped out by the First World War and shinty, with its ranks of young fit men, was hit hard. One battle in particular cut a devastating swathe – the Battle of Festubert in France in May 1915. Among the 16,000 British soldiers killed in ten days of fighting in that battle were the cream of both the 1913 and 1914 Camanachd Cup winning teams. In 1914, the Camanachd Cup was won by Kingussie, still today one of the biggest teams in shinty. Five of the 1914 team failed to come home, including the captain, William MacGillivray. The 1913 winners, Beauly, lost 25 men, including the captain Alastair Paterson and his brother Donald – hit by a sniper during the battle after stopping to tend to two wounded men. But the story of Donald, a 23-year-old lance corporal and noted piper, has a touching aftermath. “Years and years later his niece found his pipes and a tune he had written for Beauly Shinty Club during the war,” says Steven. The bagpipes, still with blood on them, had been retrieved from the battlefield and sent back to Donald’s family along with a tune he had somehow managed to write while in the trenches and stored away. It was a poignant moment when the song was first performed, more than 80 years after it was first written. The pipes are now played by a descendant of Donald.

The game also helped to sustain those sent to war – camans were sent out to troops in the Second World War and it was played by captured prisoners of war, including Stalag IXc (a German prisoner-of-war camp for Allied soldiers in World War II). And the Scottish diaspora helped to spread shinty further afield as Scots brought the game to their new homes – ice hockey is said to have been started by Scottish immigrants to Nova Scotia who started playing the game on skates on frozen lakes.

In the 19th century it was widely played all across Britain – the English football team Nottingham Forest was founded by shinty players and the Manchester Camanachd Club was formed in 1875 -before football and rugby took over and it returned to its Highland heart. The difficulties of finding jobs and housing in the Highlands in modern times, leading to rural de-population especially of young people, hits shinty as much as any other part of Highland life. But Steven says shinty also helps to bind communities together. “We need to retain families who will have children growing up in the area, we have to hold on to them. Shinty plays a large part in maintaining our rural areas – our youth grow up and represent their communities and people take a great pride in that.”

What is Shinty?

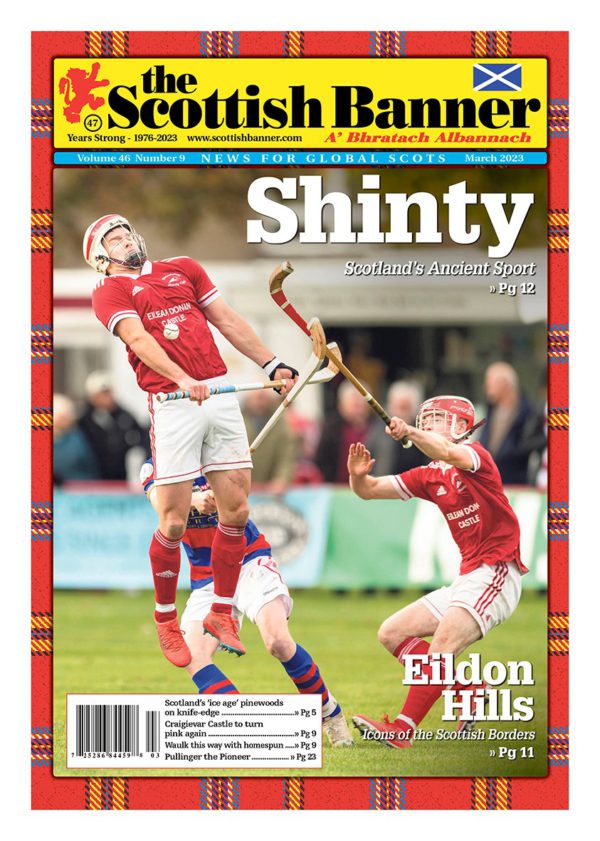

Competing for a high ball; Marc MacLachlan (Lovat) and Robert Mabon (Kingussie). 2022 Tulloch Homes Camanachd Cup Final, Lovat v Kingussie, played at The Dell, Kingussie.

The game starts with the throw up – the referee throws the ball into the air at the centre of the pitch and two players grapple for it in the air with their sticks. The object is to get the ball into the opposed side’s net by dribbling it, passing it or hitting it through the air – unlike hockey, the stick is allowed above shoulder height and shoulder-to-shoulder tackles are allowed. But bashing your opponent’s stick with your stick is called hacking and is a foul.

Helmets are now mandatory for under-17s and will soon become so for senior players, with many already adopting them. Even so, the game has a reputation for a high injury level compared to other sports which Steven says is somewhat undeserved. “That’s more a media reflection of people who don’t know the sport. It’s very skilful, people learn to protect themselves with the stick as well as learning how to hit the ball.”

The stick is known as a caman, coming from the word cam, Gaelic for crooked, referring to the bend at the end. Once made from whatever wood was available locally, often ash – though reportedly even from kelp on some of the islands – they are now usually laminated hickory made by a small band of specialist makers. “It is a craft industry,” says Steven. “They are usually making sticks for the community they come from.” As they are not factory produced, camans can be slightly different sizes and shapes but since the 1920s, all camans must be able to pass through a two-and-a-half inch diameter ring, which the referee used to carry with him.

All images courtesy of the Camanachd Association.

What great information. From New Zealand, a young ice hockey player is playing under contract in New Zealand. In Otago, Highland immigrants brought shinty and played on our frozen lakes, streams and rivers. So Shinty was lost in New Zealand but the offspring ice hockey is played throughout our country. In 2002 we saw a game and ducked when the ball sailed our way. Watching how the sticks were made with clamps bending hickory sticks into shape showed a craftsman’s skill. Thankyou for bringing back memories.