By: David C. Weinczok

In the May 2023 edition I reflected on five of my favourite Scottish castles following twelve years of non-stop exploration. Let’s now turn the clock back, way back, into the mists of prehistory. Scotland has tens of thousands of prehistoric sites, from intangible yet significant Mesolithic settlements hinting at the first people to walk the post-glacial landscape to massive monuments like standing stones and chambered cairns. Even if you live in central Edinburgh or Glasgow, you’re never far from something dating back 5,000 years or more. Some of the prehistoric sites chosen as my favourites, such the rock art of Kilmartin Glen and the many tales surrounding the Eildon Hills, have been covered in-depth in previous editions of the Scottish Banner. All the more reason to revisit the back catalogue!

The Dwarfie Stane, Orkney

Orkney could easily have monopolised this list, and the temptation to let it was strong. The Ring of Brodgar, Maeshowe, Taversöe Tuick, Skara Brae, the Broch of Gurness – need I go on? Yet, monuments similar enough to all of the above can be found elsewhere in Scotland. There is nothing anywhere quite like the Dwarfie Stane. At the head of Trowie Glen in Hoy, Orkney, is a solitary mass of rock. When the glaciers retreated some 12,000 years ago, they dropped this monumental erratic in their wake. Five thousand years ago, people wielding nothing but bone and stone tools hollowed it out and carved a stone bed, complete with a pillow-like ledge, inside. A block, now a few feet in front of the entrance, can plug it like a cork in a bottle of wine. Naturally, a place as strange as this became an epicentre for folklore.

One story tells of its creation by feuding giants. Another, no less than Walter Scott’s The Pirate, makes it the home of a Norse dwarf name Trolld. The Trowie Glen was home to the last of the fairy or ‘peedie’ (an Orkney Scots word meaning ‘small’) folk in Hoy, and many a local over the centuries was lured into their subterranean dwellings for what seemed like a few hours only to emerge years or decades later. The Dwarfie Stane has long been a draw for eccentrics, hence the texted carved in its side in Persian and reverse Latin by Major William Mounsey which reads, “I have sat two nights and so learnt patience”. It still is, hence my own visit, and hopefully one day your visit, too.

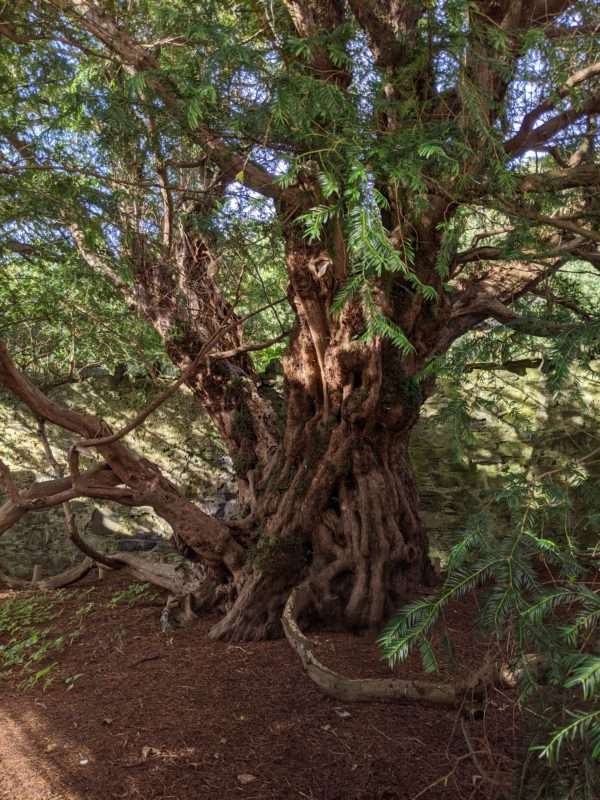

The Fortingall Yew, Perthshire

There is one very special thing about the Fortingall Yew which separates it from all other prehistoric sites in Scotland. It’s alive. At around 3,000 years old, the Fortingall Yew is one of the oldest living organisms in the world. Set within church grounds, it would have been a place of veneration for people for dozens of generations before the first whispers of Christianity were heard. Beltane fires were often lit at its base, which eventually caused the great yew to split. A report from 1769 says that it was then possible to drive a horse and carriage through the gap. Yew trees like the Fortingall specimen are revered as embodiments of the cycle of life and death. When their branches grow so long as to graze the ground, they can foster new offshoots. This may be one of the reasons why they are so often found in churchyards, given the central belief in resurrection.

More recently, the Fortingall Yew has undergone another jump across a dichotomy. In 2015 one of its branches was observed to have three berries. This is extraordinary because the Fortingall Yew is male, and yet, male yews don’t have berries. It is possible for whole yews, or at least individual branches, to change sex, and that is precisely what appears to be happening. However, the Fortingall Yew’s future could be cut short. On my most recent visit, I observed a New Age-type group praying at the tree only to then break branches from it to take as keepsakes. This type of vandalism is killing the yew, and if it is not stopped the tree will be dead as soon as 2050. I hope that it has not endured 3,000 years just to be undone by those who claim to revere it.

Achnabreck, Kilmartin Glen

Given my previous coverage of the rock art of Kilmartin Glen in the July 2022 edition of the Scottish Banner, I’ll keep this one short and sweet. Achnabreck is just one of dozens of rock art sites situated within Kilmartin Glen, an area which boast over 800 sites of archaeological significance within just a few square miles. Other standout rock art sites include Ormaig, Kilmichael Glassary, and Cairnbaan, each with their own distinctive patterns and atmospheres.

Yet it is at Achnabreck that the grandest display of rock art is on show. Carved between 6,000 to 3,500 years ago, the patterns on several sloping escarpments include rings several feet wide, deep cup marks which cradle the morning dew, and teardrop-like ‘tails’. Many are integrated into the natural features of the rock, incorporating cracks and divots into the motifs. They are best viewed at sunrise or sunset, especially in winter when the sun’s angle is low and catches every groove. No one knows what they mean, but that only deepens the wonder of being here. A lifetime could be spent trying to observe and understand the carvings in Kilmartin Glen alone (indeed several have). Some things will forever elude us, and Achnabreck teaches us that there is a certain magic in not knowing.

Kingarth Standing Stones, Bute

This is one category which could easily have been cornered by an example from Orkney, but in lieu of the many possibilities from further north, my mind kept circling – pardon the pun – back to a much less-well known example from the Isle of Bute. At Kingarth in the south of the island you will find three very unusual standing stones which I like to call the Three Weird Sisters. They were once part of a much larger stone circle, but only these three remain. They are composed of conglomerate, with one of the stones – distinctly red in hue – almost looking as though it was an arts and crafts project consisting of compressed quartz and gravel. White quartz is prominent on these stones and was used in funerary and megalithic monuments throughout the shores of the Firth of Clyde due to its shimmering nature.

While they may not be the most dramatic standing stones in Scotland, or even in Argyll and Bute, they provide fascinating insights into why such places were created and how their changing environments can alter our perception of them. For instance, most of Bute’s standing stones are positioned at valley terminals, almost like ‘gateways’. Furthermore, a book from 1893 shows the stones being enclosed by tall trees. This was the case when I visited them in 2016, lending them an air of secrecy and seclusion. Yet, these trees were far from ancient – they were a plantation, and when I returned in 2022 the stones stood instead in an open, stump-filled field visible from afar. This entirely changed the experience of visiting them, as it became possible to see what other sites they are intervisible with today and likely would have been when they were raised. It’s little insights like this which make some places stand out despite their superficial shortcomings.

The Eildon Hills, Scottish Borders

At first, the choice of the Eildon Hills may seem a strange one. After all, there is very little upon them made by people from any era which is still tangible. The reason why the Eildons resonate is due partly to their innate beauty, and to their role as a centre of gravity for countless other historic sites and stories in their literal and metaphorical shadow. One of few exceptions to the lack of tangible remains are the outlines of earthen ramparts atop the summit of Eildon Hill North, which was once the site of the largest hillfort in Scotland.

The summit was used as a gathering place since at least the Bronze Age, with room enough for up to 3,000 people to assemble – more than the modern population of Melrose. The relationship between this great hillfort and the huge Roman fort of Trimontium, which is swallowed by the shadow of Eildon Hill North as the sun sets, remains up for debate. Like Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh, the Eildons are said to be ‘hollow hills’ containing unimaginable wealth and the hidden realm of the fairy folk. Thomas the Rhymer, the renowned prophet of the Borders, gained his gift of prophecy through a seven year-long visit to this hidden kingdom. Another Borderer shrouded in mystery, Michael Scott, is said to have created them during an escapade with a demon. Of course, Walter Scott merits a second mention here as the Eildons were a beloved part of his life in and stories from the Borders. Looking out to them from the majestic lookout point of Scott’s View, it is easy to understand why.

Main photo: The Eildon Hills.