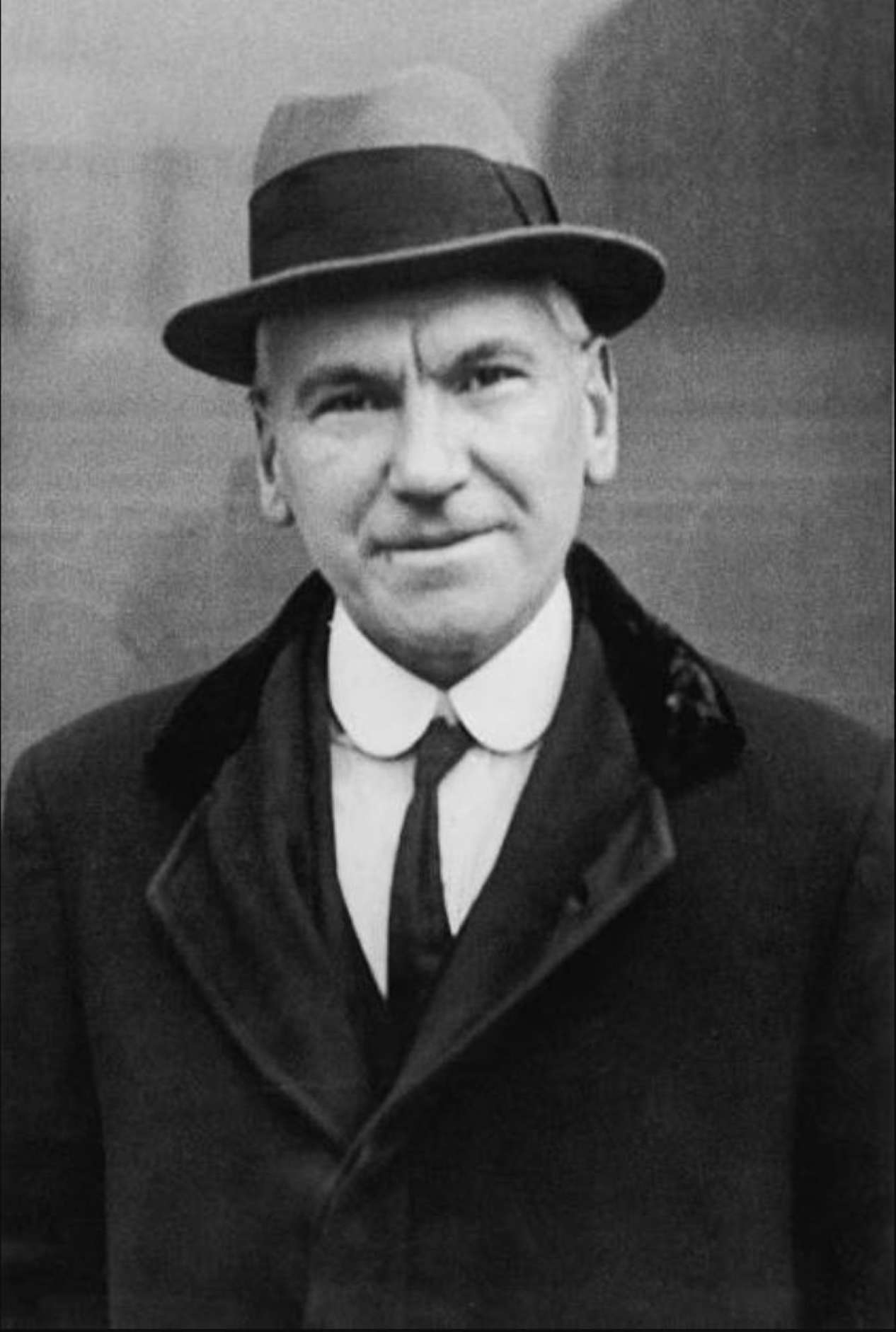

This year marks 100 years since the death of John Maclean, “the most dangerous man in Britain” and “Lenin’s man in Scotland”. A Glaswegian born of Highland parents, he was the leading light in the Red Clydeside era. He died at just aged 44 from pneumonia after he’d given his only overcoat to a destitute man. His funeral was one of the largest ever in Glasgow and he was considered both a political pariah and champion of the Scottish working class, as Judy Vickers explains.

On a chilly December day in Glasgow 100 years ago, thousands of people joined a four-mile funeral procession from Eglington Toll to Eastwood Cemetery. Thousands more lined the streets to watch the mourners pass in what is still believed to be the biggest turnout for a funeral ever in the city. The crowds were there to say farewell to John MacLean, dubbed by British Military Intelligence as “the most dangerous man in Britain” but a much-loved hero to the ordinary folk of the city and beyond for his tireless work campaigning for workers’ rights during the famous Red Clydeside era of the early 20th century.

Zeal for reform and revolution

MacLean had been a Communist and a fierce believer in education. Hundreds passed through his evening classes, which at one point he was holding every night of the week on top of his day job, learning about industrial history and economics with Marx as the main textbook. He was opposed to the First World War and the British Empire, views which led him to be imprisoned numerous times, spells which sapped his health, speeding his early death at the age of just 44. He was said to be an electrifying speaker, his 75-minute speech at his trial in 1918 is legendary, and his summer holidays were spent touring Scotland, from Lewis to Hawick, giving impassioned speeches on street corners and outside factories.

His zeal for reform and revolution sprang from his early life, which was a perfect illustration of so many woes of the day. Both his parents had been victims of the 19th Clearances in Scotland, where landlords in rural areas had removed tenants – sometimes forcibly – from their homes and the land they had worked, often for generations, to fill them with more profitable and less labour-intensive sheep. His mother, Anne, came from the village of Corpach in the Highlands, his father Daniel from the Isle of Mull. A potter, Daniel briefly worked in Bo’ness before taking up work at a pottery in Pollockshaws, then on the outskirts of Glasgow, where the family settled.

Tales of injustice

Tales of injustice were part of his childhood, but his upbringing was typical of many at that time – three of his siblings died in infancy and his father died when he was just nine from silicosis (“potter’s lung”) from his working conditions. His brother contracted TB and eventually emigrated to South Africa, joining the many swathes who left Scotland to seek better lives during the early 20th century. Daniel and Anne were far from the only ones to descend on Glasgow during the 19th and early 20th centuries; the city expanded rapidly as casualties of the Clearances and Irish immigration swelled numbers. Housing became difficult to come by and was often poor and unsanitary when it could be found, with landlords dividing tenements into ever-more squalid homes.

After his father’s death, John worked several part-time jobs in order to continue his education and qualified as a teacher, gaining an MA from the University of Glasgow. He taught in schools in south Glasgow, but his real passions were revealed after the school gates closed – teaching in evening classes to workers, joining and helping to organise left-wing and Marxist groups, writing pamphlets and supporting workers to form trade unions, and fight for better wages and conditions. This was a time of unrest in Scotland. The landmark Singer sewing machine factory strike in 1911 was broken by the authorities but this only intensified workers’ efforts rather than quash them. But it was MacLean’s opposition to the First World War, which broke out in 1914, which led to his more serious clashes with the authorities, including several periods in prison and the loss of his teaching job.

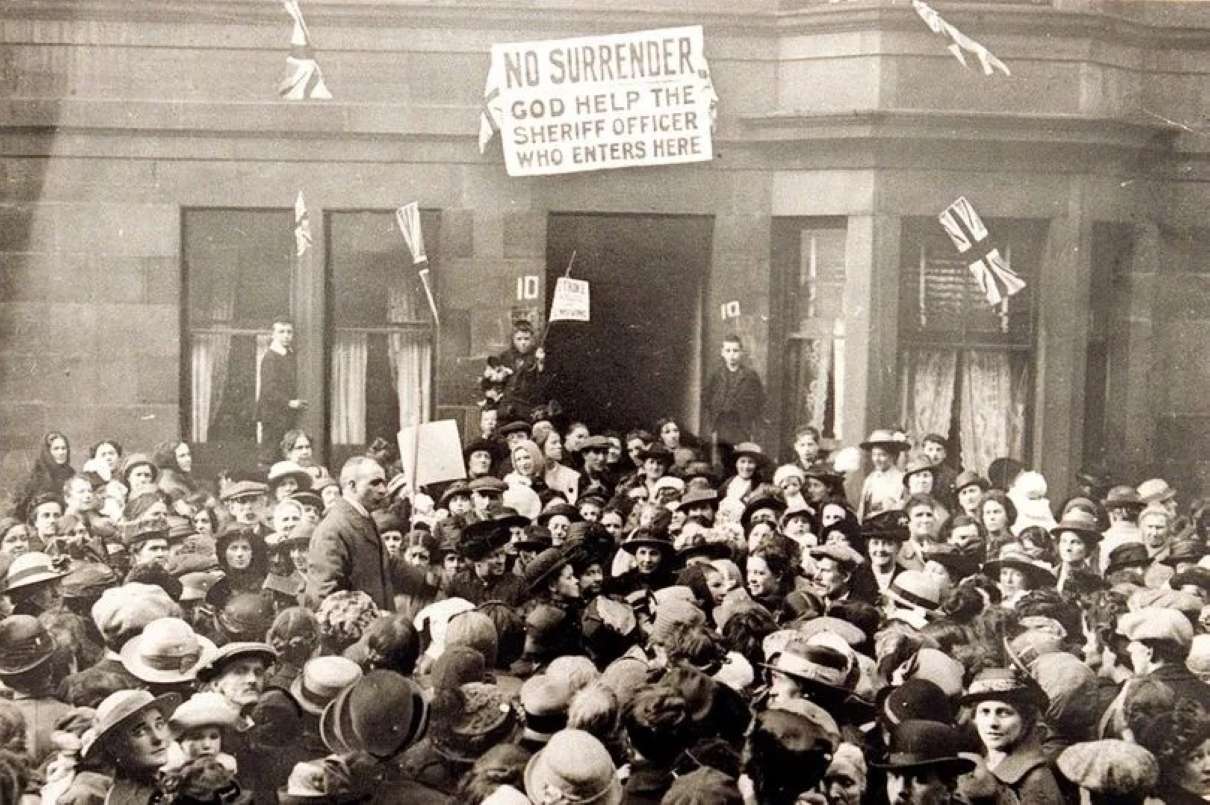

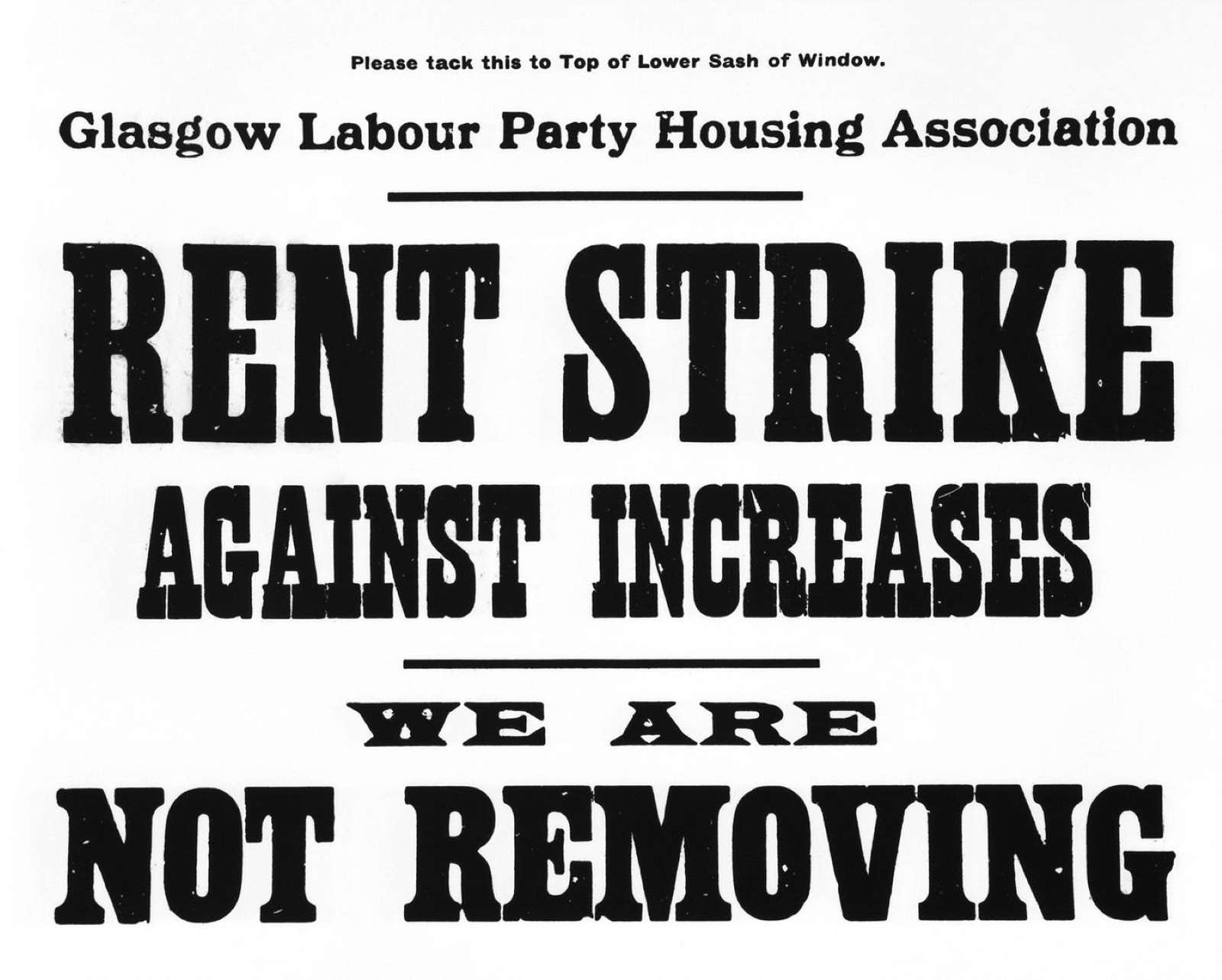

A 1915 strike at munitions factory Weirs of Cathcart – an unofficial strike as the Defence of the Realm Act had made such industrial action illegal and which was led by shop stewards who were former pupils of MacLean’s – failed but helped to hike tensions. When rents were increased, MacLean helped organise a rent strike by the women of Govan and enlisted the support of the men in the shipyards and factories. As the agitation spread across the city, MacLean was arrested and charged with making statements likely to prejudice recruiting to the wartime military.

His penalty was a short imprisonment, but it also cost him his job at Lorne Street Primary School. In the November of that year, as he worked his notice on his job, 18 men were called to court for refusing to pay their increased rents. MacLean was carried shoulder-high by the crowd to the court where he addressed 10,000 people and called for a general strike if the rent rises went ahead. The alarmed authorities pressed through a Rent Restriction Act.

Famous pioneer of working-class education

In 1916 he was arrested again and sentenced to three years in prison with hard labour after being found guilty of sedition although he was released after 15 months following mass demonstrations, including a protest by thousands when Prime Minister Lloyd George visited Glasgow. In 1918, following the Russian Revolution of the previous year, MacLean was named the Bolshevik Consul for Scotland by Lenin. Such an appointment was never likely to endear him to the British authorities, which were increasingly alarmed at the prospect of revolt and MacLean was arrested again.

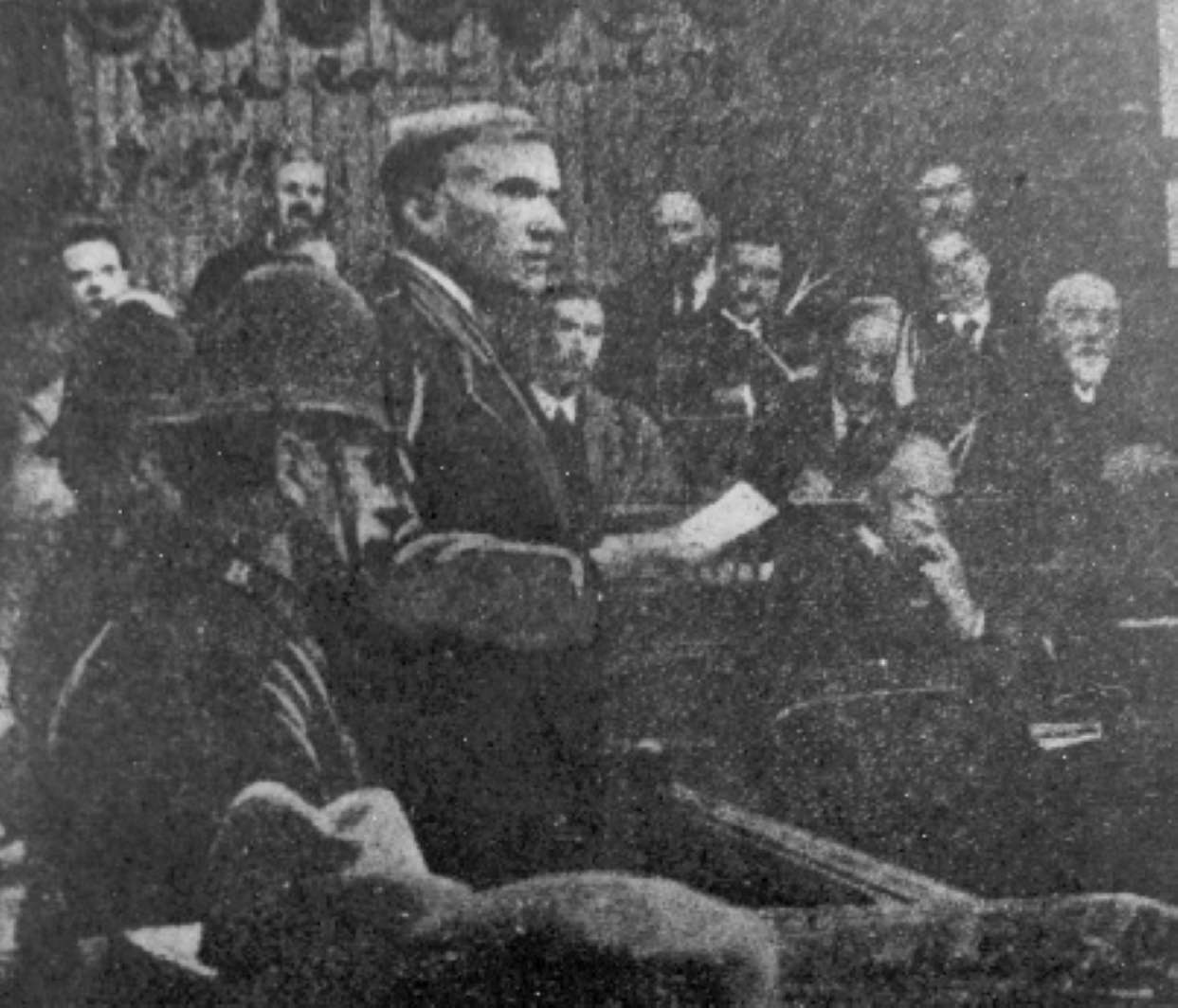

At his trial in May of that year, he gave a 75-minute impassioned speech in defence of his views, coining the term “underclass” and declaring: “I consider capitalism the most infamous, bloody and evil system that mankind has ever witnessed. I wish no harm to any human being, but I, as one man, am going to exercise my freedom of speech. No human being on the face of the earth, no government is going to take from me my right to speak, my right to protest against wrong, my right to do everything that is for the benefit of mankind. I am not here, then, as the accused; I am here as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot,” he told the court. He was sentenced to five years and incarcerated in Peterhead Prison in Aberdeenshire, where he was force fed by tube through hunger strikes, severely affected his health. More mass protests saw him released in December 1918, following the November Armistice, and thousands turned out to welcome him home to Glasgow.

He continued to campaign, but his health deteriorated, and he collapsed while giving a speech in Glasgow in November 1923 – he had given his overcoat away to a destitute Jamaican man. He had to be carried off the open-air platform and died on November 30th from double pneumonia.

The colourful era of the Red Clydesiders became an iconic part of Scotland’s political history but MacLean, one of its leading lights, is less remembered. He was, however, commemorated with a stamp issued by the Soviet Union in 1979 and with a 6ft cairn of granite near his birthplace, which was unveiled in 1973, 50 years after his death. The inscription on it describes him as a “famous pioneer of working-class education” and at the unveiling ceremony poet Hugh MacDiarmid described him as “next to Burns, the greatest ever Scot”.

Main photo: John MacLean in 1918. Photo: Hulton Archive, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.