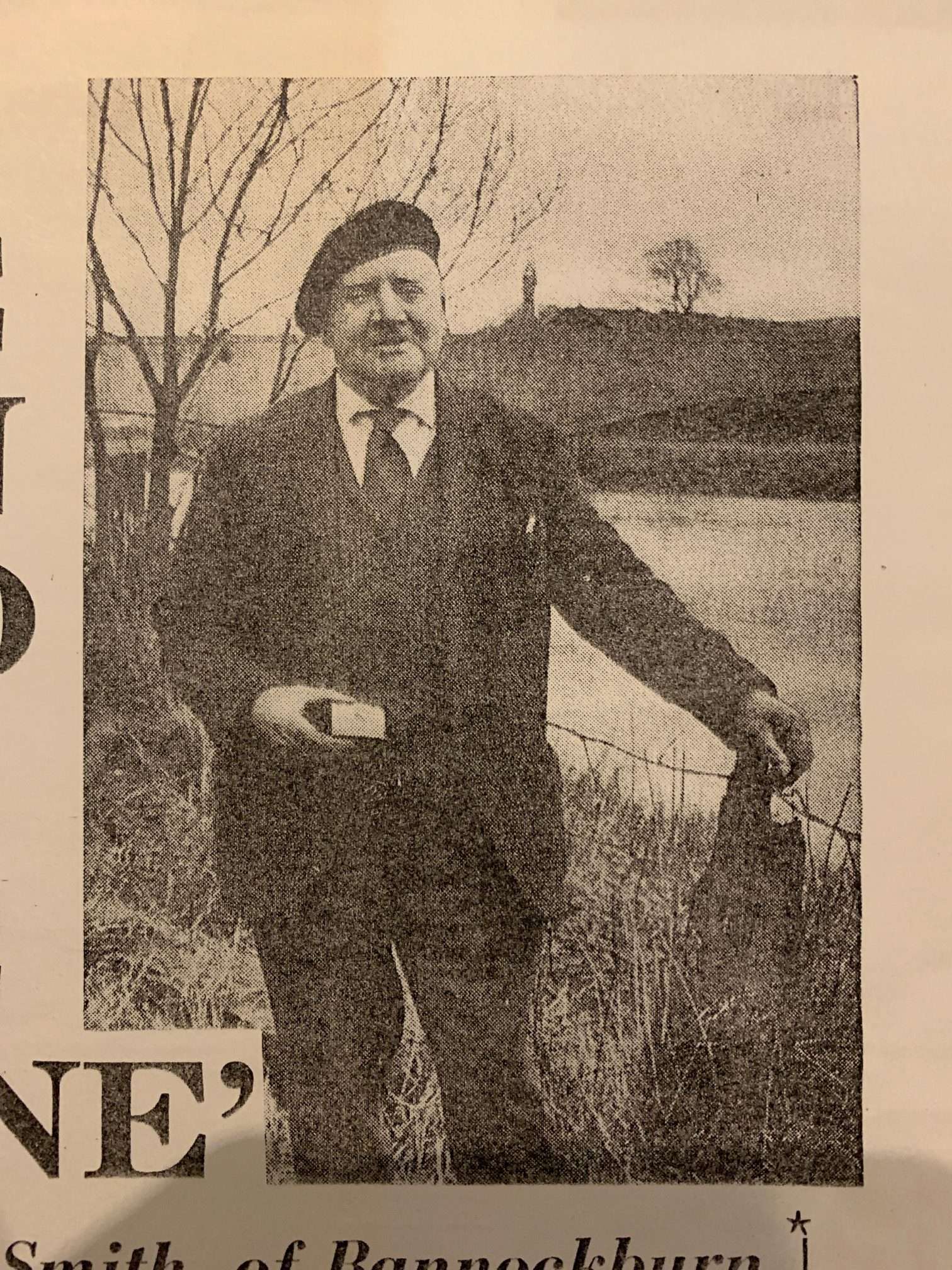

A massive manhunt was sparked after the stone was removed from Westminster Abbey by four students, and Tam Smith from Bannockburn played his part in the now infamous episode Neil Drysdale reports.

Tam Smith was as busy as ever in his engineering workshop early in 1951. But, as he took a breather, his eyes focused on a newspaper which conveyed how police forces across Britain were searching for the Stone of Destiny, which had been removed from Westminster Abbey by four students on Christmas Day a few weeks earlier. As a staunch nationalist, Tam was interested in the story, not least because of the manner in which the youngsters, Ian Hamilton, Gavin Vernon, Kay Matheson – who hailed from Wester Ross, and Alan Stuart, had managed to “liberate” the Stone of Scone – the ancient artefact upon which Scottish monarchs had been crowned – despite a massive manhunt by the authorities.

Suddenly, though, there was a visitor in his presence. It was a senior police officer, a decent chap who enjoyed a natter, but was well aware of his compatriot’s political leanings and thought it would be funny to raise the subject of the missing stone. “Okay, Tam, where is it?” he asked, as the prelude to the pair sharing a laugh. If only he had known that the prized item was sitting just a few feet away! In the aftermath of the heist, the monument, dating back to the 13th century, had become too hot to handle, but one of Tam’s close friends called at his workshop in Stirling early in January with his car and trailer and asked: “Are you 100% Scotsman?” Quick as a flash, he replied: “I am 200%, if that is possible. Bring it in. I had guessed that the cargo on his trailer was the stone.”

He was proud of his part in it

He spoke to the People’s Journal in 1967, omitting some of the more sensitive details to avoid implicating others, but Tam’s exploits became part of his family lore. And his grandson, former Aberdeen GP, Ken Lawton, has talked about the background to one of the more remarkable incidents in Scottish history. He said: “Tam was born in the Gorbals (in Glasgow) in 1890 and he always had a great social conscience and I can remember him with a sticker on his car saying ‘It’s Scotland’s Oil’ in the 1970s. He was a true nationalist and was quite happy to play a role in keeping the stone hidden from the authorities, despite all their efforts to track down it down.

They even hired a psychic

“In his terms, the stone hadn’t been stolen, but brought back to where it belonged in the first place, and he even took a little bit of the artefact which he kept in a matchbox in a secret drawer and which he would show a few of us at family gatherings. Months passed and the police grew a little desperate. They even tried out a Dutch psychic, who told them that the stone was hidden near a graveyard and close to a small bridge – and both of these fitted the location of my grandfather’s workshop. But they had no joy in their hunt and Tam always thought it was appropriate that here was the stone hidden in a place which just happened to be in Bannockburn.”

Eventually, in April 1951, the police received a message and the stone was discovered on the site of the High Altar at Arbroath Abbey, where, in 1320, the assertion of Scottish nationhood had been made in the Declaration of Arbroath. And, although it was returned to Westminster Abbey early in 1952 – more than two years after Hamilton and his colleagues launched their audacious plan – no action was taken against the quartet of students because it was deemed it would not be in the national interest to punish them in the courts. To some, they were “heroes”, to one or two others, they were ‘traitors’ and that political divide has never healed. Indeed, an argument broke out in recent weeks when it emerged that a “missing” fragment of the Stone of Destiny had been kept out of the public gaze at the SNP’s headquarters.

Party politics spilled over again

Shadow secretary for business, economic growth and tourism Murdo Fraser MSP said: “It may be fanciful to restore this fragment to the Stone of Destiny, given the claim that it results from the damage caused when it was stolen in the 1950s. The crucial thing is to get it on public view, and not kept in a cupboard in an SNP office. People will be delighted to see it alongside the stone in Perth, in the splendid new museum which has been funded thanks to the UK government.”

However, another perspective was offered by the Alba MP, Kenny MacAskill, who is convinced that the events of more than 70 years ago made a powerful statement. He said: “The stone is part of Scottish history, both past and more recently. The actions of those who stole or liberated it were more than just a jolly jape. It was an attempt to keep Scottish identity alive and to push for Scotland’s distinct nationhood. Those involved deserve enormous credit, because there must have been huge risks for them at the time.

It is a part of who we are as Scots

“The steps later taken, even by Michael Forsyth, an arch unionist (the Stone of Destiny was officially returned to Scotland in 1996 and put on display in Edinburgh Castle) were doubtless partly triggered by that and were a recognition of its symbolic importance. Whilst a growing number of people in Scotland now veer towards republicanism it doesn’t diminish the history and status of the stone. It is part of who we are as Scots. As for a fragment of it going to Perth Museum, then why not?”

Ken Lawton has spoken about his grandfather Tam Smith’s role in hiding the Stone of Destiny in 1950. Ken Lawton has no doubt that Tam, who died in 1987 at the grand old age of 97, and who celebrated his platinum (70th) wedding anniversary to Janet the year before, would be delighted that the stone was back home. And, for him at least, a small part of it never went away.

Tam was buried with the fragment

He said: “My grandfather was a humble man, but he took his responsibilities seriously when it came to the stone. He never identified who it was who came to his yard back in 1950 and, although he wasn’t part of the plot, he was proud to be a link in the chain.” Ken added: “He was also thrilled he had a small fragment of the stone in his possession from when he was its guardian and I’m sure it was buried with him in Bannockburn Cemetery. It was a different time then, but I’m glad that his story is finally being told.”

Main photo: A young Ian Hamilton (centre).

This is a wonderful article.