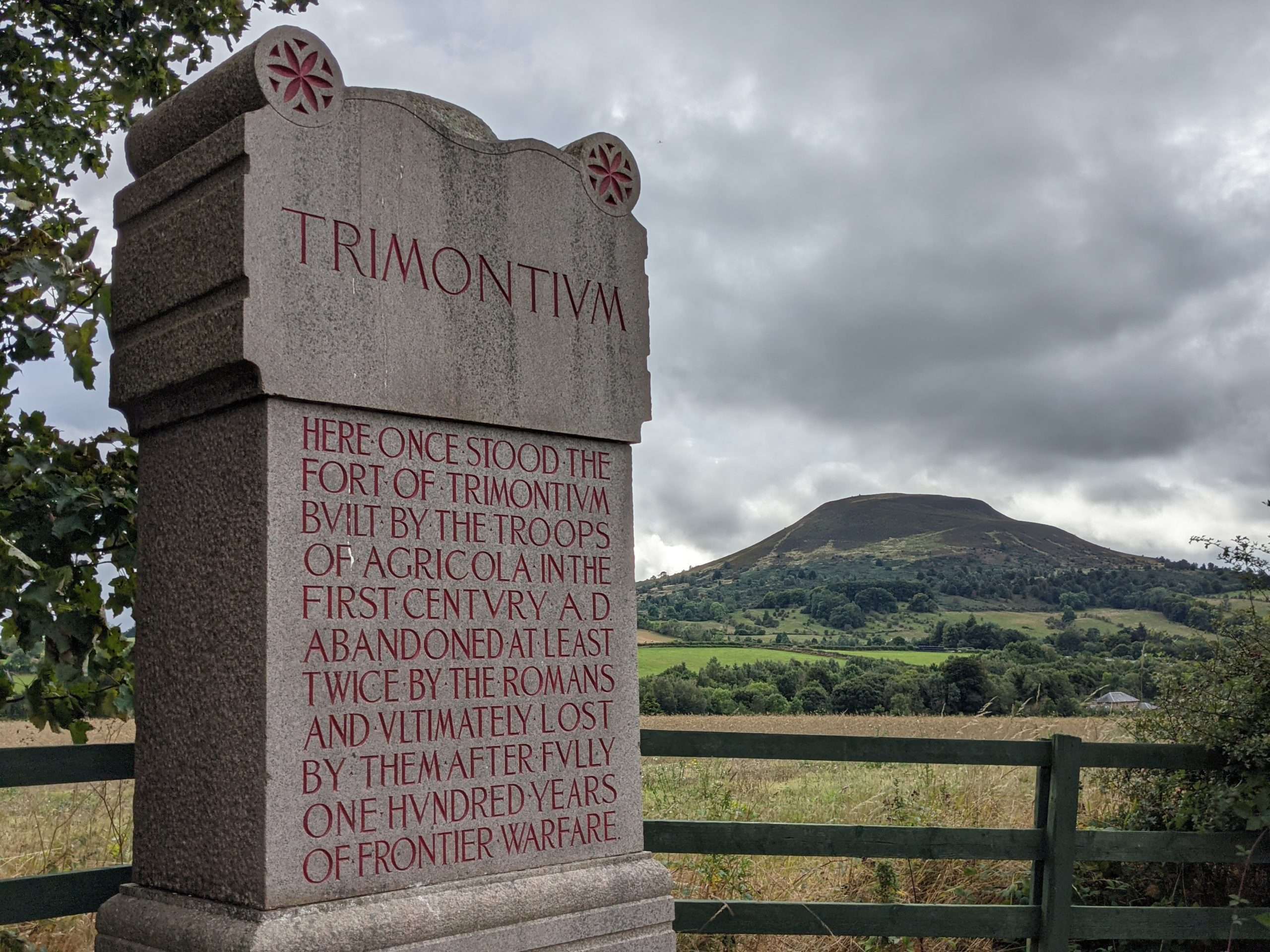

It began with a skeleton. Not long ago, that skeleton was given a face. Now, after nearly 2,000 years in the soils of a Roman fort, we finally know the place that face called home. The skeleton in question was unearthed at Trimontium Roman fort along the River Tweed near Melrose in the Scottish Borders. Meaning ‘place of the three hills’ after the Eildon Hills looming over it, Trimontium was a massive auxiliary fort which at times marked the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire in Britain.

The Trimontium Trust, who run Trimontium Museum in Melrose and conduct archaeological research into the Roman invasions of Scotland, have announced the results of new dating and isotope analysis into the identity of this ‘Trimontium Man’. He was no legionary conqueror, but a local born and raised in the Scottish Borders. The question that remains is: why was his body buried within a Roman fort?

The lands that would one day become Scotland

First built by the forces of Agricola, who went on to victory at the Battle of Mons Graupius, in the late 70s AD, Trimontium was occupied on and off until 211 AD when the death of Emperor Septimius Severus caused a total Roman withdrawal from the lands that would one day become Scotland. The fort had the northernmost confirmed amphitheatre in the Roman Empire, a bathhouse, barracks blocks, a luxurious mansion, and four annexes dedicated to manufacturing, civilian housing, and training. The skeleton’s identity was a mystery within a mystery. It was found in one of the 107 pits discovered at Trimontium during excavations led by Melrose solicitor James Curle between 1905 and 1910. These pits were no mere dips – some were more like wells, up to 36 feet deep. Their contents were astonishing, fuelling speculation about the fort’s ultimate fate to this very day. The exact circumstances of their creation remains unknown.

The pits were stuffed to the brim with everything you can imagine, and some things you’d rather not. Huge volumes of masonry from the fort itself were tumbled into them. Prized possessions including iron weapons and armour, brooches, rings and leather shoes were mixed in among animal bones, shattered pottery, and several separate human remains. Seventeen horse skulls were recovered from a single pit, all of them seemingly killed by a blow to the head shortly before they were dumped into the pits.

What could possibly have driven such destruction? The contents of the pits date from at least two different periods of occupation, the 80s AD and 180s AD. In both cases, Trimontium was abandoned – or overwhelmed – as the Romans withdrew south to consolidate and focus on threats on other frontiers of the empire. Were the contents of the pits deposited in good order, perhaps by the garrison grimly cutting their losses and preventing anything of value from falling into native hands? Or could they have been filled in the wake of a violent overthrow of the fort by the vengeful Selgovae or Votadini tribes who had previously bent under the Roman yoke?

The debate still rages, and we may never know the truth. Now, however, we know intimate details about the life of Trimontium Man. Analysis coordinated by Professor Derek Hamilton of the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC) as part of the Francis Crick Institute’s 1000 Ancient Genomes from Great Britain project has confirmed that Trimontium Man’s life coincided with the first period of the fort’s occupation, some time before 120 AD. He was born and raised somewhere in a swathe stretching from Moffat in the southwest to the Lammermuir Hills in the north-east.

A son of the Borders

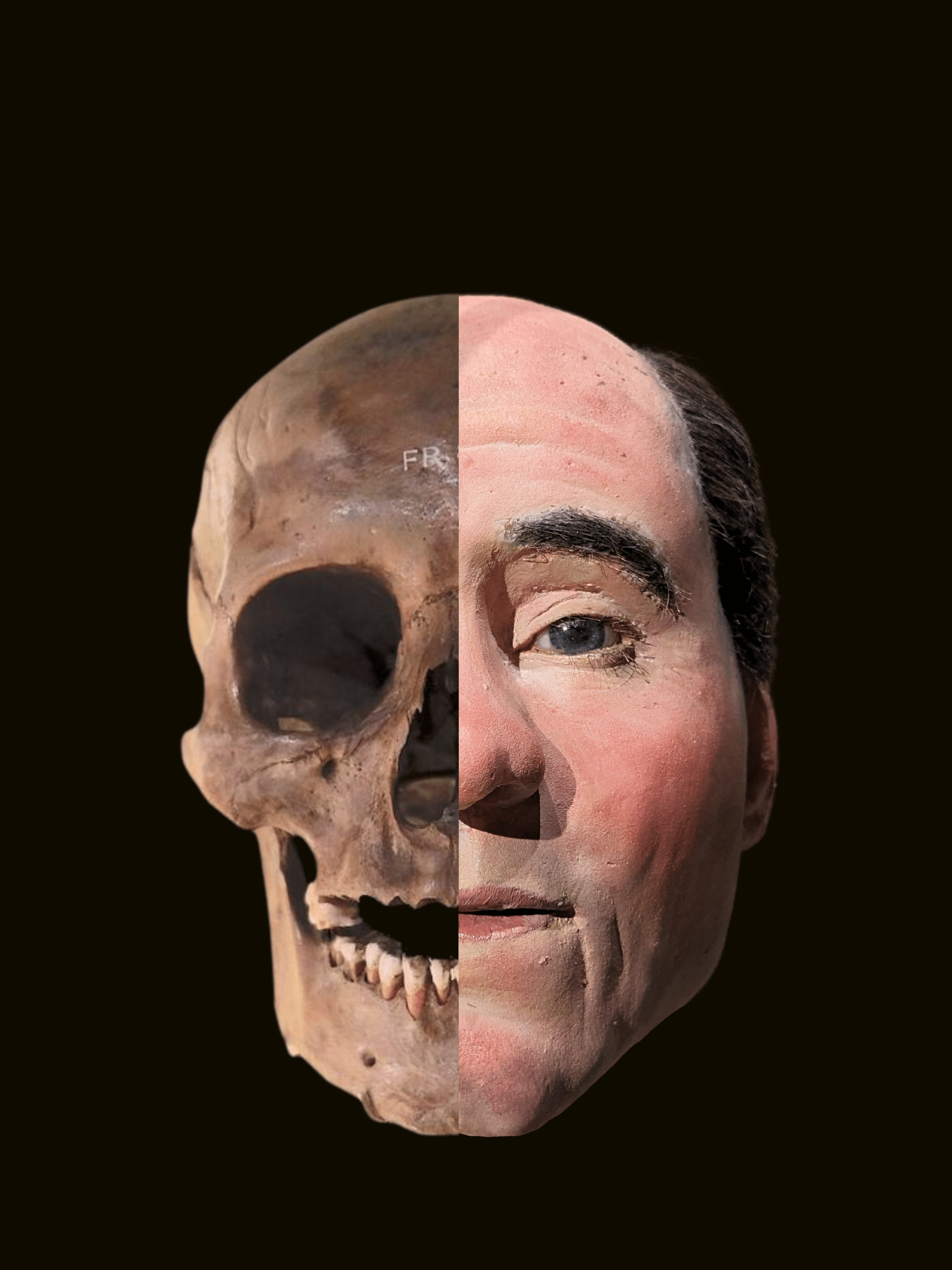

A facial reconstruction for Trimontium Man was previously made by Professor Caroline Wilkinson. His face is weathered but kindly, with small features and a bald pate – the kind of face you’ll see in most any pub or while walking along any British high street today. Strontium isotope analysis of one of his teeth identified him as between 36 to 45 years old at the time of his death. His diet consisted almost entirely of land-based plants and animals despite having the River Tweed and North Sea nearby, an unusual trend of minimal fish consumption we see across early Scotland through into the Pictish period. He had periodontal disease with several abscesses and an overbite on the right side, so he must have been no stranger to pain and discomfort.

As for how his life ended, we can only guess. He could have been a civilian trading with the soldiers of the fort who was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Perhaps he was a warrior or dignitary executed by the Romans to send a message, or killed simply out of blind malice as the soldiers prepared to retreat to Hadrian’s Wall. It was, after all, common practice for Romans to execute prisoners prior to withdrawing from a region. Intriguingly, an iron spearhead was found alongside his skeleton, but this may have shifted from elsewhere in the pit and may have no direct connection to Trimontium Man. Whatever the truth, Trimontium Museum is telling as much of the story as it can through continuing research and interpretation. Many of the finds from Trimontium’s pits are on display at the museum, as well as at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. There is a special pride in Trimontium Man in Melrose – he was, after all, one of ours, a son of the Borders.

By: David C. Weinczok