Few things bring a little warmth and comfort in the dark depths of a Scottish winter like a dram of whisky sipped by a crackling fire. When Hogmanay comes round, whisky shared in a quaich has brought people together for centuries. Some poor souls, however, nearly had to go without after a little incident which went down in the ballads as the ‘Battle of Corrymuckloch’.

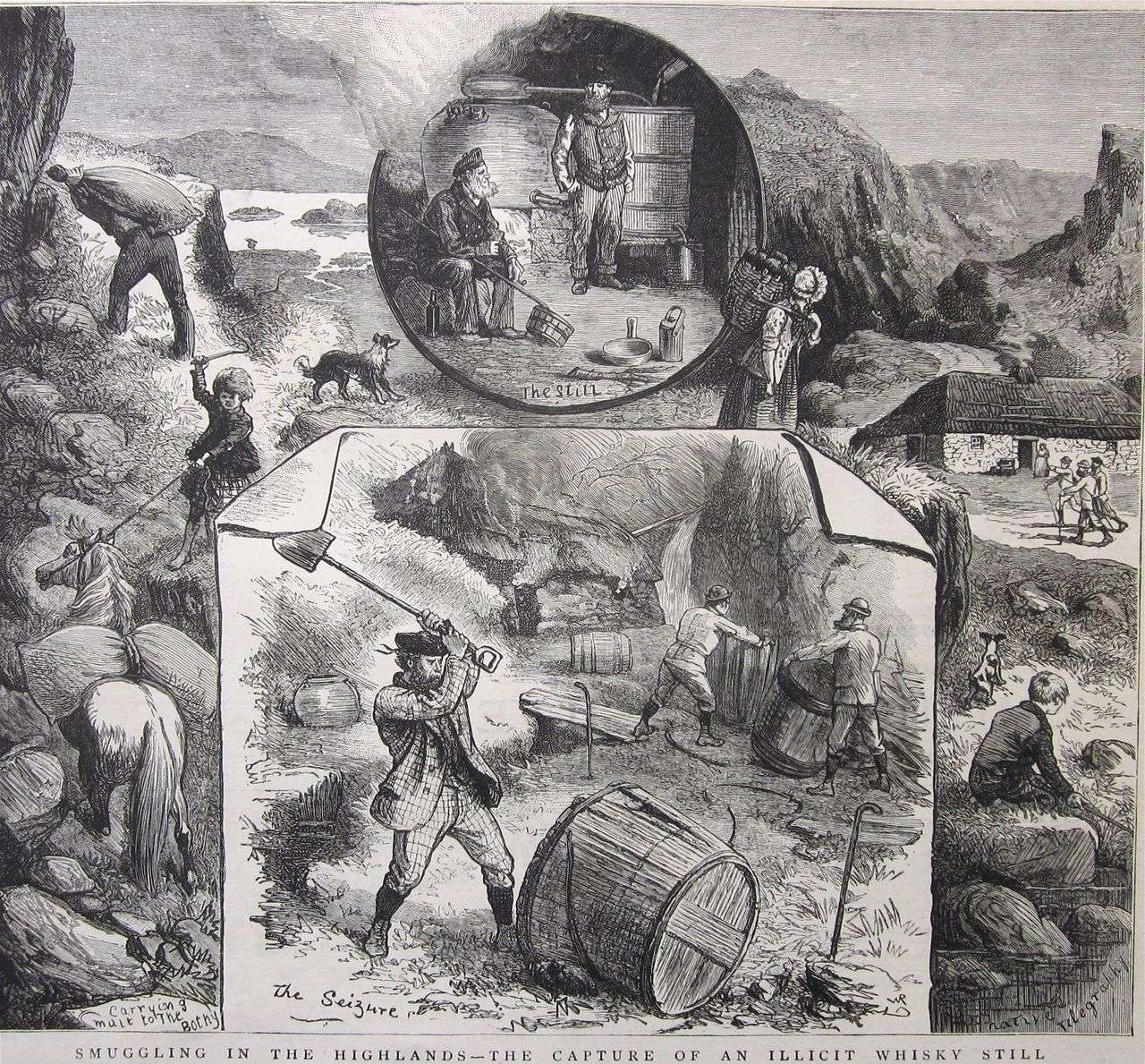

The early 19th century saw the mainstreaming of whisky as never before. Even King George IV learned to enjoy a dram following his visit to Edinburgh in 1822, allegedly even preferring the illicitly-produced whisky, commonly known as ‘mountain dew’ or ‘moonlight’, over the officially-certified ‘Parliamentary’ variety. This booming demand in the south led many in the Highlands to produce their own whisky in illegal stills, often engaging in cat-and-mouse games with the excisemen and dragoons who were dispatched into the countryside to track and charge them.

Sma’ Glen

Smugglers would make the journey to Lowland towns along the old drove roads and hill passes little-known or monitored by government officials. One of the main arteries for the movement of cattle and whisky was the Sma’ Glen, a narrow pass in Glen Almond used by travellers for centuries to reach the trysts, markets, and inns of Crieff, Falkirk, and beyond. On approach to the Sma’ Glen is a broad expanse of bog, heather, hillocks, and hollows known as Corrymuckloch, which once hosted an inn notorious for its popularity among smugglers. It was here, a few days before Christmas in 1831, that a group of smugglers was intercepted. Laden with barrels containing potent and untaxed whisky, a group of around 20 men with carts were headed for the mouth of the Sma’ Glen. Unbeknown to them, a troop of Royal Scots Greys, no less, had decided to seize the initiative by riding out from Perth to destroy any illicit stills they could find among the hidden places of Breadalbane. The two groups must have been astonished by their luck, or lack thereof, of running directly into each other along the road!

In a series of interviews in the 1950s, Donald Dow of Tomantianda, a native Gaelic-speaker, described the scene: “A kinsman of mine, Thomas Calmanach, of the Balnabodach family, was – how would you say – in charge of the convoy. He was ahead of them. He recognised the smell of cigar smoke, a thing not usual in the country at all, except for rich people. He suspected trouble and went back. There were fifteen carts laden with whisky. He made them unhitch the horses and tie them to the carts. He, himself, and his men went forward to meet the Scots Greys. Thomas Alasdair, was a tremendously big and powerful man. He was six feet and five inches tall, with bones in him like a horse’s. He had a stick, an oak cudgel, and in the first attack he struck the officer, half killing him. He fell out of his saddle and Thomas grabbed his sword, then killed the Captain. He also killed another two or three, and the rest of them fled. They had horses and they escaped, and they got through with the whisky.”

An anecdote from The Beauties of Upper Strathearn, published in 1870, tells of the fate of one of the participants. Years after the ‘battle’, an old drover on his way back north from Falkirk stopped at the scene of the scrap. When his companions asked what gave him pause, he revealed that he was one of the Scots Greys who had “so ingloriously fallen” that day. After recovering from his wounds, he was nonetheless unable to continue serving as a soldier and decided instead to “turn his sabre into a shepherd’s crook”. A little illicit hustling was nothing new for the inhabitants of the Breadalbane glens.

The 19th century saw a population boom across much of the Highlands which was not matched by agricultural outputs, leaving many desperate for any scrap of food or income that they could get. Dougall McMillan of Amulree, Ontario (named after the settlement just north of Corrymuckloch) was descended from people who left or were cleared from Glen Quaich in the early 19th century. Interviewed in the 1930s, Dougall told how his grandfather decided to leave after a gamekeeper employed by the Earl of Breadalbane entered his home unannounced at the very moment that a poached deer was cooking over the fire!

Fleeing from the excisemen

Fleeing from the excisemen was a fairly common motivation for emigrants to places like Canada. William Crerar, also of Ontario, told how his grandfather, John Crerar, was “a whisky smuggler all his life in the old country from the time he grew to manhood” who emigrated because “the excisemen were after him.” To avoid apprehension, Crerar changed his surname – he was, in fact, a McIntosh. This was easily done in a period when there were very few ways to verify anyone’s surname, and indeed when few enough people even had one.

Many emigrants borrowed or invented surnames during the process of emigration, or had their names recorded incorrectly by customs officials who were either indifferent to their duties or unable to speak or understand Gaelic. This makes the genealogist’s work much more complicated than it already is. The Battle of Corrymuckloch may have faded into obscurity among the countless grander clashes of the past, but it is very much remembered in folk traditions. Contemporary Scottish folk band Findlay Napier and the Bar Room Mountaineers immortalised it in a ballad, singing:

And ere the action it was ower

There fell a horseman on the plain

Quo Sandy unto Donald syne

“Ye’ve killed ane o the bearded men,”

But he gat up an left his horse

And aff tae Amulree he flew

Left the rest tae dae their best

As they had done at Waterloo.

By: David C. Weinczok

Main photo: 19th century engraving by Sir Edwin Landseer of an ‘illicit Scottish whiskey still’.