Celebrating Marion Campbell, Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray, and Dorothy Marshall.

Popular depictions of archaeology would have you believe that it’s the quintessential man’s game – look no further than the archetype of Indiana Jones, or the renowned stories of the men who discovered the likes of the city of Troy, Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, or the Sutton Hoo burials.

However, right from the field’s inception women have been among the most influential and important contributors to it. Far too often these formative figures have been overlooked, and it was not until well into the 20th century that many professional societies even permitted women to join as members.

Scottish archaeology, and the related field of ethnography, has benefitted from the grit and genius of pioneering women working at all levels since day one. Three in particular have emerged again and again in my own research into Scotland’s past, and it is they I wish to celebrate here – Marion Campbell of Argyll, Lady Evelyn Murray of Perthshire, and Dorothy Marshall of Bute.

Marion Campbell (1919 – 2000)

Kilmartin Glen is among the most significant archaeological landscapes in northern Europe, and no one has done more to reveal and revel in its wonders than Marion Campbell. Marion’s own life is a history book in itself. She served in the Second World War and suffered an injury from the bombings of the Clydebank Blitz, which left her in often acute pain for the rest of her days. This did not stop her from carrying out tireless manual excavations of archaeological sites throughout Kilmartin Glen and Mid Argyll, often in very hard to access places. She served as a district councillor for the Scottish National Party for twenty years, and her donation of various discoveries established the invaluable collection now held at Kilmartin Museum.

Along with Mary Sandeman, with whom Marion lived at Kilberry Castle for forty years, she identified over 350 sites of interest in the first systematic survey of Kilmartin Glen. Their work together created a blueprint for future research in Mid Argyll, including investigations into key sites like the hillfort of Dunadd, the Nether Largie standing stones, and the extraordinary Neolithic rock art panel of Achnabreac. Marion possessed not only a gift for scholarship, but of lyrical writing.

Her description of the vast peat bog of the Mhòine Mhór as “…a quaking salt-bog barely above the tidemark” has stayed with me ever since reading it, as has the description that follows: “…the name has the sough of winds in it. Veils of sleet drive over withered grasses and hang in cold walls of glass around the highest rock.” She wrote several children’s books, a rare feat for someone so involved in academic research. Each morning, Marion woke early to feed the animals in her garden, who she referred to as “the friends”. If we all aspire to even half the talent, determination, and kindness which Marion embodied, the world would be a much better place, indeed.

Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray (1868 – 1940)

Lady Murray’s life on paper sounds a fairytale. Daughter of the 7th Duke of Atholl based at Blair Castle, had she walked a conventional path for someone of that status she could have led a very charmed and untroubled life. However, her fierce will and intellect compelled her to completely eschew the social expectations of the time – marriage, childbearing, and the social graces – in favour of adventure and obsessive study.

In all seasons and weathers, the young Lady Murray could be found wandering Highland Perthshire in search of stories told in Gaelic, which was then fading from everyday use. She collected 241 tales told by native speakers, many of which had never been written down before. Her work is a veritable treasure trove of ethnology, folklore, and historical memory, some of it preserving a local dialect of Gaelic which does not survive anywhere else.

In her teens she suffered a severe illness, likely typhoid, whose symptoms followed her throughout her life, leading to periods of severe physical and mental distress including partial paralysis in her legs and arms. Still, Evelyn refused to limit the hours of her studies, often working late into the night at breakneck pace. She worked so assiduously that, fearing for her eyesight, her caretaker (for her parents had long since given up trying to reign her in) forbid her from reading and writing by gaslight – which she continued doing anyway.

My own lived experience has given me great admiration for Evelyn’s impassioned spirit. Chronic health issues have sometimes waylaid me, but despite this I have visited thousands of historic sites across Scotland and have put a few oral historians’ tales to writing for the first time. A calling is a calling, and whenever I need a little inspiration in the face of limitations, I think of Lady Murray and all that she achieved in spite of them.

Dorothy Marshall (1900 – 1992)

Dorothy Marshall is to archaeology in Bute what Marion Campbell is to it in Kilmartin Glen – definitive. Her parents, Jean Binnie and John Marshall, encouraged all their daughters to pursue higher learning in the sciences. Dorothy’s sisters, Margaret and Sheina, were awarded OBEs, and Dorothy was awarded an MBE in 1981. Dorothy served as a ‘Lumberjill’ in the Women’s Timber Corps during the First World War before studying archaeology in London and excavating in Cyprus, Jericho, Petra, and Jerusalem. She served as a multi-time President of the Buteshire Natural History Society, delivered Meals on Wheels well into her 80s, and participated in excavations in Bute right into her very final years.

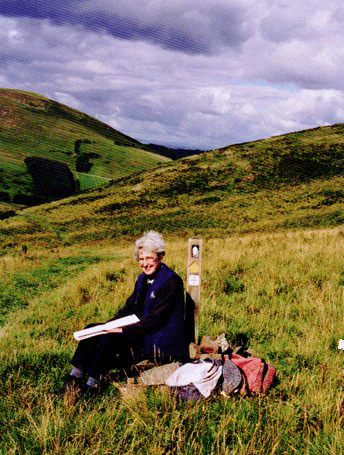

Her most famous excavation was of the cist burial of a high-status woman on the island of Inchmarnock off Bute dated to around 2,000 BCE, whom Dorothy dubbed the ‘Queen of the Inch’. Her grave yielded a stunning jet necklace, a type of status symbol found in elite graves throughout Argyll. Other excavations include the Norse houses at the hillfort of Dunagoil in southwest Bute, the Neolithic cairn of Glenvoidean in rugged northwest Bute, and numerous finds of the ever-enigmatic prehistoric carved stone balls. The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, of which Dorothy was a Fellow, awards the Dorothy Marshall Medal every three years to an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to Scottish archaeology.

Many in Bute today fondly remember Dorothy, for she was no ivory tower-bound researcher but an active and beloved member of the community. This was illustrated to me most vividly while conducting research at Bute Museum in Rothesay. I asked curator Anne Spiers, who knew Dorothy personally and worked closely with her, to describe her legacy. “The spirit of Dorothy is very much with us here”, she said. “She loved the idea of what future technologies would make possible, excavating a site without laying a finger on it. Any time something is found here in Bute, I wonder what Dorothy would make of it.” When I asked Anne what Dorothy’s favourite archaeological site in Bute was, she gave an answer which will ring true for anyone who finds inherent joy and meaning in their vocation: “Whichever one she was at, at the time!”

Text by David C. Weinczok.

Main photo: Glenvoidean Cairn in Bute excavated by Dorothy Marshall.