On the night of March 24, 1944, scores of Allied POWs crept their way through a cramped tunnel ten metres underground in one of the most incredible escapes of World War II, the ‘Great Escape’ from Stalag Luft III, in Nazi-occupied Poland. Scottish RAF pilot Alistair Thompson McDonald was amongst the 76 escapees and one of the few to make it home. Six decades on Neil Drysdale remembers these brave men who were unlike any other Tom, Dick and Harry.

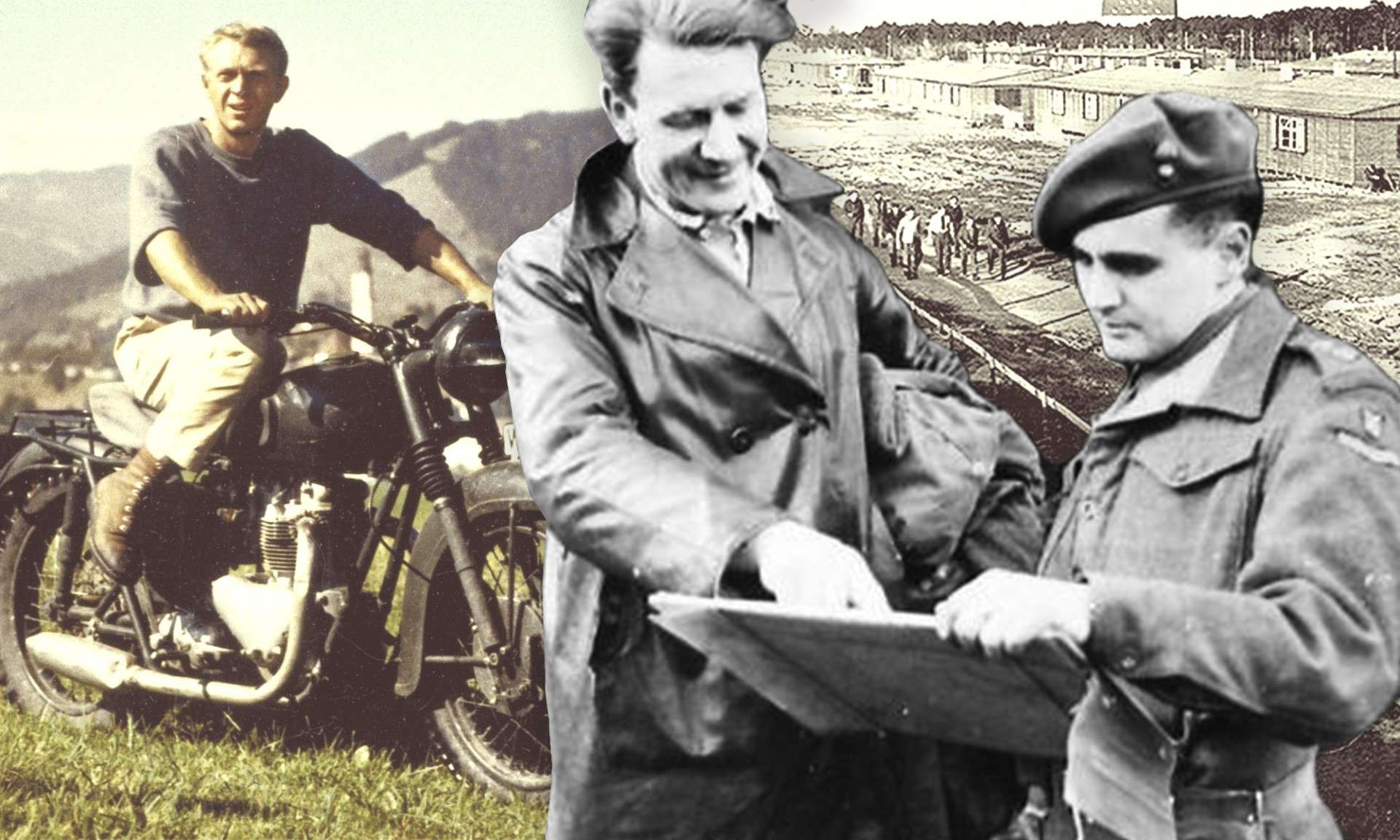

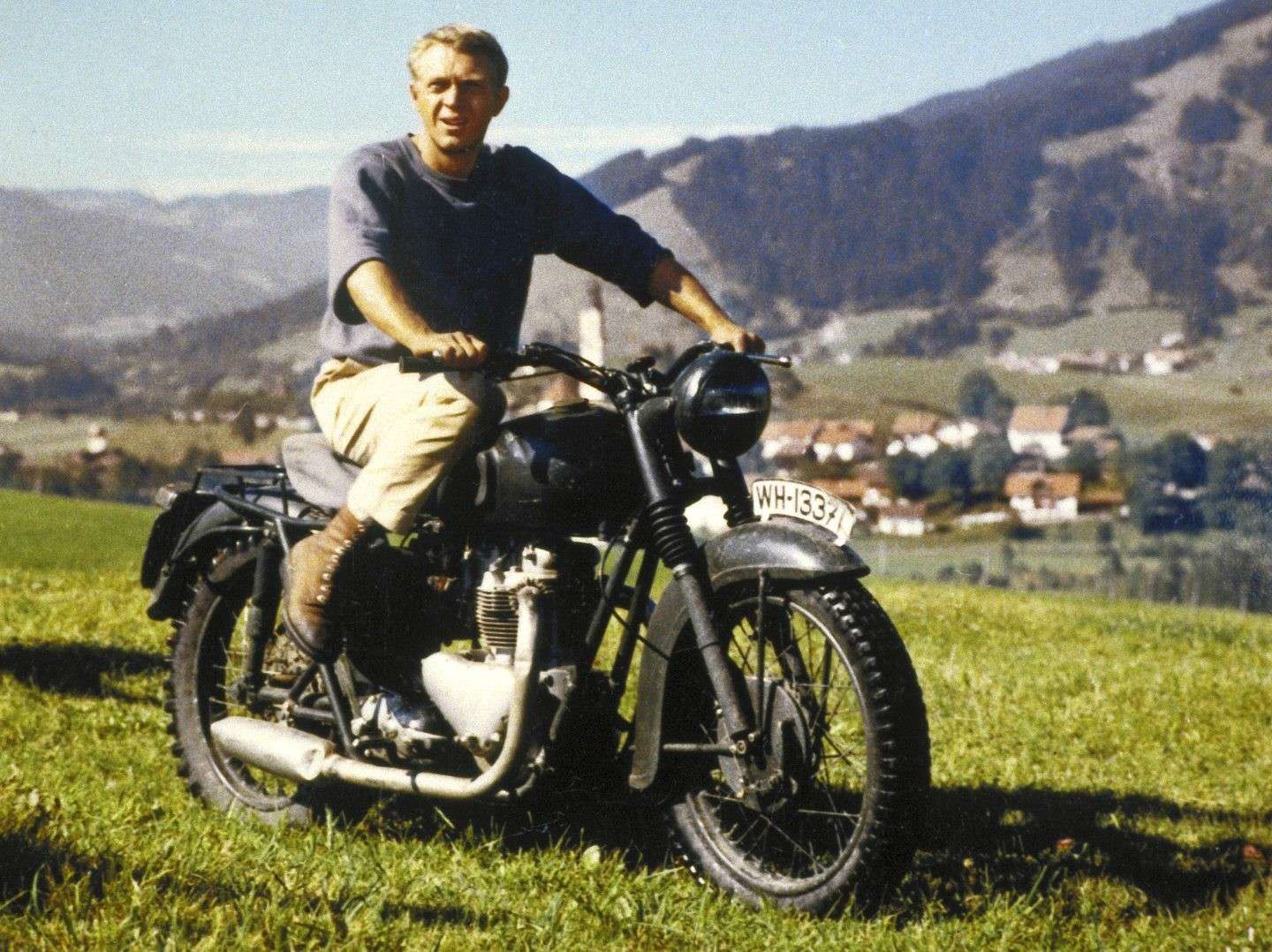

He was the Scot who survived one of the most famous prison break-outs of the Second World War. Indeed, there can’t be many people who haven’t watched The Great Escape since it was released in 1963, not least to marvel at Steve McQueen’s motorbike stunts.

Yet, the real-life story of the 76 Allied PoWs, who devised a daring scheme to tunnel their way out of Stalag Luft 3, was every bit as nail-biting. And it had a tragic climax when the Nazis murdered 50 of the escapees after they had been recaptured and only three eluded their captives and gained their freedom.

Alistair Thompson McDonald

Alistair Thompson McDonald was among those in the escape bid and despite his liberation being short-lived, he used his wits to escape yet again and safely returned to Blighty. Yet mystery still surrounds this tough-as-teak character, born in Bishopmills near Elgin in 1907. There are precious few photographs of him, nor tributes to his heroism. And, when he was killed in a commercial air disaster in 1965, there was only one brief obituary which failed to mention that he had been part of the original Great Escape. So, who was this enigmatic Scot with a passion for flight? The youngest of three children – with an older brother and sister, Ian and Mildred – Alistair grew up in Moray and relished playing rugby and golf, but had a restless streak. At just 18 years old, he enlisted in the Tank Corps of the Territorial Army, to whom he gave his occupation as apprentice land surveyor.

However, three years later, he set off on a P&O steamship called the Naldera bound for Malaya. At this point, he listed his occupation as civil engineer and worked on a tea plantation. But, soon enough, Alistair was back in Britain and, continuing this tale of the unexpected, became the manager of the Regal Cinema in Southport in the mid-to-late 1930s. We would probably still be in the dark about his activities after he joined the RAF in 1940, but for the meticulous research carried out by Scottish history teacher, Bill Robertson, whose own great-grandfather, John Conway, was also in Stalag Luft 3. Bill was fascinated by how McDonald lied about his age – claiming he was born in 1913 – so that he would be eligible to take part in flying missions against the Luftwaffe.

Craggy little Scot

He was transferred to Coastal Command where he flew Spitfires on reconnaissance sorties and rapidly made a name for himself for two distinct reasons. Firstly, he was a “hell of a pilot”. Secondly, he had the reputation of being a “craggy little Scot” who wouldn’t take nonsense from anybody. In March 1942, McDonald’s fortunes changed in the space of a few hours. On his way back from a mission, his unarmed plane was intercepted by a Messerschmitt (German fighter aircraft). He bailed out successfully in the last minutes before the aircraft crashed, but was picked up near a farmhouse and taken prisoner by the Germans.

He was escorted to the Luftwaffe HQ in Amsterdam and met up with a few other RAF prisoners. Then, after being kept in solitary confinement for 18 days, he was interrogated three times and transferred to Stalag Luft 3. Mr Robertson said: “As a P0W, he took part in nine escape tunnels and what he described as ‘an abortive gate crash.’ He also attempted to get out by cutting through the wire along with a New Zealand pilot called Ernest Clow. McDonald was active on the escape committee. According to the camp history, he was one of the prisoners who was involved in receiving and sending coded letters back to the UK. Prisoners asked, in coded letters home, for particular items that would help them to escape such as maps, money, and clothes.”

Tom, Dick and Harry

There was no shortage of ingenuity as the mass escape initiative cranked into gear. Cigarette packets were deployed to carry vital information. Radios were manufactured from basic materials. In 1943, under the leadership of Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, known as Big X, the PoWs started digging three large tunnels known as Tom, Dick and Harry. These were 30ft deep in an attempt to avoid German detection and were designed to run more than 300ft into woods outside the camp. The prisoners begged, borrowed and stole equipment that enabled them to line the tunnels with wood and ventilate the tunnels with primitive air conditioning. They also made civilian clothes, maps, compasses and German passes to help them escape.

Everything went well for several months, but tunnel Tom was discovered by the Germans in September 1943 just as it had reached the woods. Dick was abandoned for storage, but the prisoners pushed on with Harry, which was ready in early 1944. And, on the night of March 24, 76 RAF personnel broke out of the camp. A few hours later, it was being discussed by Hitler and the German High Command. The Fuhrer demanded retribution. But what was McDonald doing amid this clamour?

In his testimony about the murders of the escapees, he subsequently confirmed he was one of the later men out of the tunnel which the prisoners codenamed Harry. Most of the PoWs headed to the nearest railway station, intending to catch trains from there, but several of their comrades resolved to see how far they could travel on foot. Unfortunately, the knee-deep, slushy snow forced the escapers onto the roads. Cold, hungry and disorientated, the majority were rounded up fairly quickly. McDonald said: “I was carrying false papers and wearing civilian clothes. I was recaptured by the Landwacht, who made a half-hearted attempt to beat me up.”

A sad postscript

These men were now in a desperate position. Hitler had been outraged on discovering the extent of the breakout and demanded swift retribution. It was obvious to many in the German ranks that their adversaries would never accept their incarceration and keep striving to escape: the latter was in the Allies’ DNA. Mr Robertson said: “The men were interrogated by the Gestapo and those who survived recalled the threats made against them. Other officers were told they would be made to disappear. For his part, McDonald said: ‘I was able to eat my false papers and sew RAF buttons onto my greatcoat (which meant he was regarded as a military prisoner); and this may have been the reason why I was not shot’.

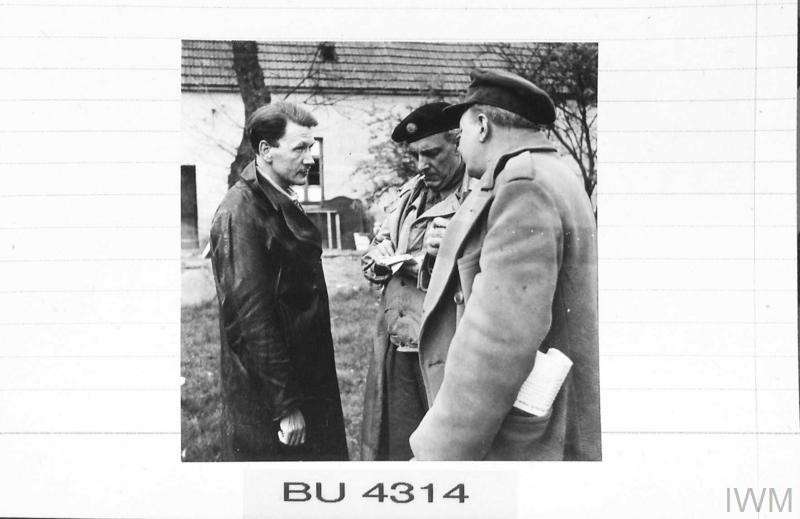

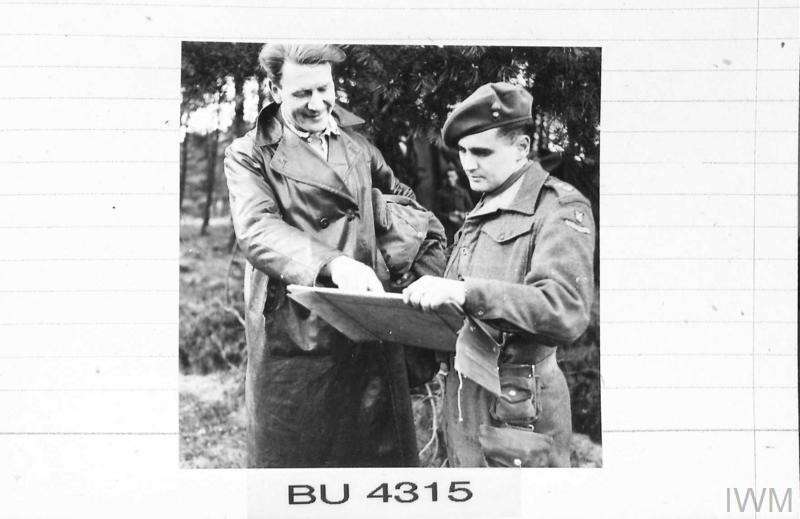

After he was returned to the camp, McDonald was eventually evacuated along with the rest of the men to begin marching west ahead of the advancing Russians. After reaching Marlag Nord near Bremen, he managed to escape while disguised as a labourer, using clothes he had acquired from a French woman. She had supplied him with ‘a complete outfit of French worker’s clothing’. Suitably attired, he made his way to British lines where he was eventually picked up by a unit of King’s Own Scottish Borderers from the 52nd Lowland Division in April 1945.”

He was able to return to Blighty to celebrate VE Day the following month and must have imagined life would never be as tumultuous again. But there was a sad postscript. For a while, he thrived on civvy street and rejoiced at being reunited with his sister and brother, the latter of whom had served with the RASC in the Middle East and Italy. McDonald married in 1947 and lived in Edinburgh, where he and his wife had three children and ran a self-service laundry business in Leith.

But, as Bill said: “In October 1965, he left Edinburgh to fly to London Heathrow aboard a Vickers Vanguard operated by BEA. There was reduced visibility due to fog at Heathrow. After two unsuccessful attempts to land, the pilot requested to circle the airport hoping for a break in the fog. At this point, the pilot and co-pilot made a series of errors, and the Vanguard hit the runway about 2,600 feet from the threshold. All 36 people on board were killed. McDonald’s participation in the Great Escape – which had recently become a big-budget success – barely merited a mention. The Coventry Evening Telegraph described him simply as a ‘Battle of Britain pilot’. He was shot down over Holland and helped organise a mass escape from a German prisoner-of-war camp.”

And that was it. Thankfully, 60 years after his death, this hero is finally being remembered.