The Fife town of Glenrothes was ‘born’ on 30th June 1948. It was Scotland’s second new town and became the first in Scotland to appoint its own artist to specially create public art. Today the town houses tens of thousands of people, has a strong connection to the electronics industry, as well as a much loved African animal, as Judy Vickers explains.

In 1950, the population stood at just 1,000 people, living in a couple of hamlets and farm steadings scattered across the area. By 1960, the population of the new town of Glenrothes had shot up to 12,500 and was growing rapidly – latest figures show there are almost 40,000 people living there today. This year the Fife town celebrates its 75th anniversary and to mark the occasion, an exhibition charting its history is being held at the Kingdom Centre in the town and a new sculpture – of a hippo, which has become the unlikely symbol of the town – is being unveiled.

Coal mining

The town was founded in June 1948 as the second of Scotland’s new towns under the New Towns Act of 1946 – the first was East Kilbride. Unlike East Kilbride and several other new towns which were created during this period, Glenrothes was not designed to home the overspill population from Glasgow, Scotland’s largest city. Instead the idea was to construct homes for the workers at the new nearby Rothes Colliery, planned to be one of the country’s new “superpits”, producing 5,000 tons of coal a day and lasting for 100 years. Coal mining in the area dates back to the 13th century but it was only in the post-Second World War era, with the drive for security of energy, that mass production was planned.

Shafts had already been sunk by the time Glenrothes was founded but the mine suffered flooding and geological problems. Plans for the town specified that one in eight of its inhabitants should be miners and although the colliery was opened with great fanfare by the late Queen Elizabeth II in 1958, a year after it finally began producing coal, it only lasted another four years, before closing in 1962 as one of the National Coal Board’s most spectacular failures. The town that was built for it, however, proved far more long-lasting and successful. Located between the villages of Leslie, Thornton and Markinch, it was named after the Earl of Rothes who owned most of the land which the town was built on – Glen was added to avoid confusion with Rothes, a town on the banks of the river Spey in Moray near Elgin. The town was almost called Westwood, after Joe Westwood, the then Secretary of State for Scotland, who proposed the location.

Silicon Glen

The area has long been occupied by mankind – the earliest known civilization in Glenrothes is the early Neolithic settlement of Balfarg. Ancient pottery and other artefacts dating back 4000 years BC were found here. The 3000-year-old Balfarg Henge and stone circle at Balbirnie show that the new town has some fairly ancient foundations. While the loss of mining meant the original purpose for the town was lost, it did not spell its end though, as a new industry had sprung up even before the closure of the pit. In 1958 US based Beckman Instruments choose Glenrothes over English locations for its UK plant – Glenrothes having been promoted as being perfect for electronics due to its clean air. Others followed including Hughes Microelectronics (now Raytheon), Canon, Brand-Rex (now Leviton) and Apricot Computers, making Glenrothes a key player in Scotland’s “Silicon Glen”. Many electronics firms have since relocated to places such as China but some have stayed and are still key employers in the area.

Hippos

New towns were often seen as rather soulless places with no cultural history. To combat that, Glenrothes became one of the first to appoint a town artist. It was an inspired move; not only has it made Glenrothes a centre for public art – there are more than 140 pieces in the town today produced by the official town artists and visiting creatives – but it also gave the town its curious link with hippos. The first artist was David Harding in 1968. He was employed as part of the planning department and he moved to the town with his family to better immerse himself in the place and created pieces such as Henge (1970) drawing on the town’s prehistoric links. But it was his assistant Stan Bonnar – father of TV actor Mark Bonnar – who created the first hippo sculpture, made out of concrete. It was such a hit that Harding and Bonnar made several more, positioning them around Glenrothes. The next town artist was Malcolm Robertson who added landmark pieces such as The Birds (1980) and Giant Irises, the town’s contribution to the 1988 Glasgow Garden Festival.

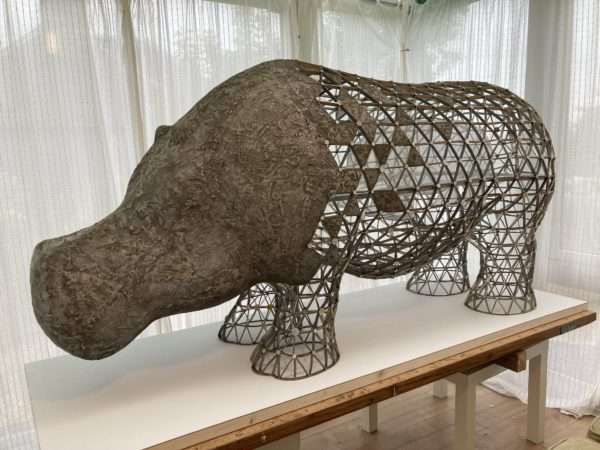

But it was the hippos which captured the town’s imagination which is why the African animal is the subject of a new sculpture for the town. The sculpture has again been created by Stan Bonnar who was persuaded out of retirement by Leviton, formerly Brand-Rex, which was marking 50 years in the town. The Disappearing Hippo follows the theme of the older hippos but highlights the plight of the creatures in the wild due to global warming and the reduction of their habitat. The frame is formed by 685 triangles cut and shaped by Stan from old tin cans.

The recycled materials and the “disappearing” theme obviously reflect 21st century concerns – instead of the original environmentally unfriendly concrete Stan has used a greener, modern alternative geopolymer concrete – with hippo dung as the binding agent. And along with the history of the town, the exhibition features the work of The Turgwe Trust, the hippo conservation charity which sent Stan the dung.

Ian Wilkie, the managing director of Leviton Network Solutions who is part of the event’s steering committee, said: “As a piece of art to commemorate the 75th birthday of Glenrothes, there could be no more fitting tribute. The fact that it has been created by the original Mr Hippo – Stan Bonnar in the year when he too turns 75 makes this even more special. But as you gaze at this hippo’s beauty here in Glenrothes, spare a thought for the plight of real hippos in the wild.”

The Glenrothes 75 Years exhibition will run at the Kingdom Centre throughout July, August and September.

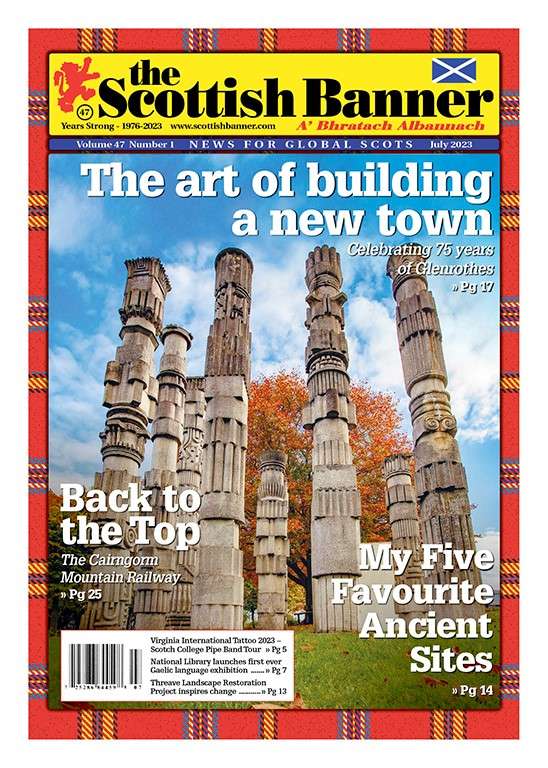

Main photo: The Dream by Malcolm Robertson, 1989.