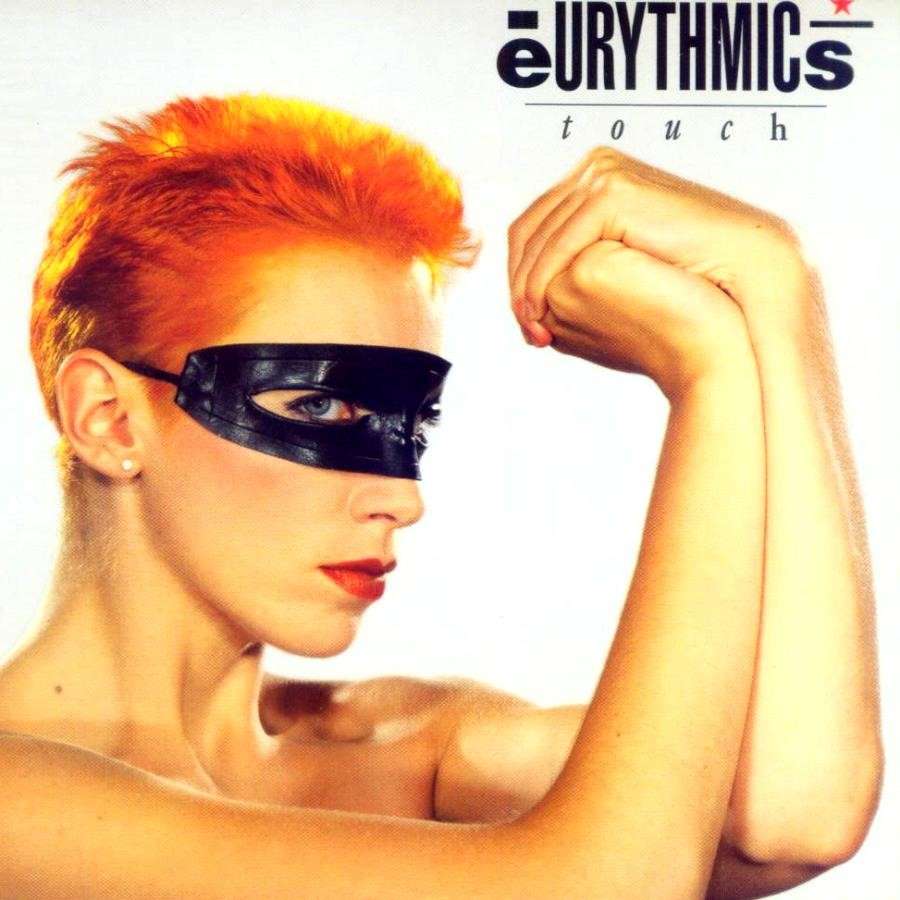

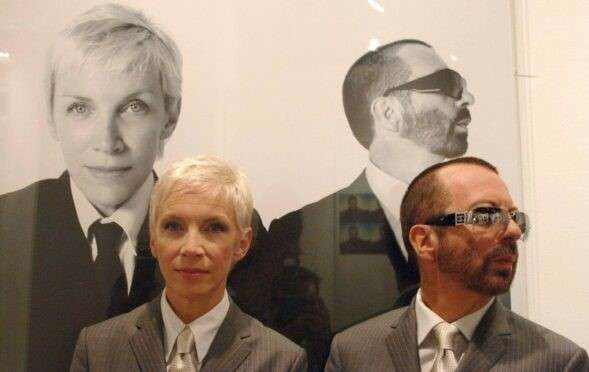

Annie Lennox has never been interested in sticking to bland platitudes or ignoring injustice. Ever since the teenager left Aberdeen High School for Girls in the 1960s and ventured to London with ambitions of orchestrating a successful music career, she has developed into one of Scotland’s greatest pop stars and a tireless activist for multiple causes. The myriad hits speak to her versatility: the androgynous video which propelled her to global stardom as one half of Eurythmics with Sweet Dreams; and the powerful voice which joined forces with Aretha Franklin in Sisters Are Doing It for Themselves.

The Granite City

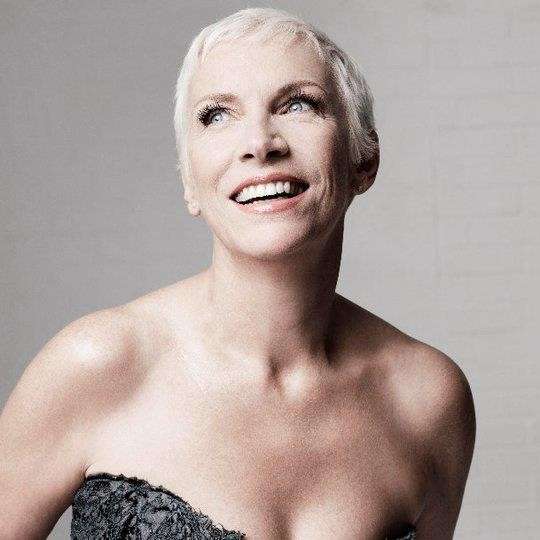

On her own, the title of her solo album, Diva, amplified the message that she was the mistress of her own destiny, whether rocking the charts with Walking on Broken Glass and Why or following it up with Medusa and No More ‘I Love You’s’. Annie has not enjoyed a comfortable relationship with Aberdeen, despite being its most famous musical daughter. On the contrary, the woman who was brought up in a two-room tenement in Hutcheon Street, has spoken out on many different issues. It hasn’t always made her friends or provided cosy conversations. But the woman who celebrated her 70th birthday on Christmas Day remains one of life’s rugged individualists.

In 1988, at the height of her success, Annie agreed to become a patron for Haddo House Hall Arts Trust. This should have been an ideal opportunity for her to indulge in a few upbeat statements about nurturing young people’s potential. Yet, while there were positive noises about her new role, there was plenty of other stuff which testified to Annie’s belief that the Granite City hadn’t done itself any favours. As she said: “I feel very distressed about the kind of ravaging that has gone on in the centre of Aberdeen and I’m very upset about it.” Even as Eurythmics were preparing for global acclaim in the early 1980s, Annie found herself in her home city battling with depression and afraid to leave her own home. Which means that anybody who listens to Sweet Dreams and regards it as an uplifting anthem is wide off the mark. On the contrary, it was a cry for help with a catchy hook.

Agoraphobia

Eurythmics bandmate Dave Stewart was forced to spend time in hospital with a collapsed lung and Annie, seeking refuge from disappointing sales of the first Eurythmics album, travelled back to her roots and began to contemplate whether she could continue with her music career. She said: “I spent a great deal of time crying. I hit rock bottom. My self-esteem dropped to an all-time low and I was suffering from agoraphobia. I couldn’t go outside the door. Whenever I did, I started having panic attacks, I would get palpitations and come out in cold sweats. It was horrible. In the end, you realise that you are devastatingly alone in the world. And no matter how much you want to get out of that sort of thing, it’s hard to crack. It has to come entirely from within yourself and eventually you have to start thinking about your own self-preservation. (As for Sweet Dreams) It’s basically me saying ‘Look at the state of us. How can it get any worse?’ It’s about surviving. It’s not a normal song so much as a weird mantra that goes round and round, but somehow it became our theme song.”

That ambivalence has embodied Annie’s career, but nobody can deny the creative vim and vigour and boundless energy which she has brought to her life on and off stage. She appeared at Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday concert in 1988; became a public supporter of Amnesty International and Greenpeace; recorded music to increase Aids awareness; and was fiercely critical of the war in Iraq in 2003. Five years later, she founded The Circle of Women, a private charitable organisation to raise funds for projects and backed the principle of an independent Scotland. Archbishop Desmond Tutu said of her: “She is one of those exemplary human beings who chose to put her success in her chosen career to work in order to benefit others.” There were similar glowing words when she sang in front of Barack Obama. And when she pushed her horizons into boosting the lives of women in Malawi. She has cared passionately about equality and enhancing women’s rights in countries where they were too often abused or disregarded.

And yet, her involvement in campaigning hasn’t been merely reserved for international matters. When oil tycoon, Sir Ian Wood, proposed a “transformational” scheme in Aberdeen’s Union Terrace Gardens in 2009, Annie wasn’t impressed by the plans. And that’s putting it mildly. Casting her gaze over what was being advocated, she described it as “architectural vandalism.” And she wasn’t finished there. As she later wrote: “The heart of my home city of Aberdeen was simply torn down. It makes my heart sick and still does. What went in its place were these vile, concrete monstrosities. Don’t get me wrong – I love modern architecture, but not when the historical is replaced by the goddam awful. Go to Florence, Paris or Rome. They don’t have a problem living with antiquity.”

Thrawn

In many respects, Annie is a contradictory character. A private person with a desire to fight for her beliefs in public; a Scot with an internationalist streak who often seems happier abroad; and somebody whose charismatic performances mask a deep shyness.So, it was hardly surprising she was stunned when she delved into her family background in the BBC programme Who Do You Think You Are? In 2012. It emerged that her great-grandmother, Isabella McHardy, was hauled before the Kirk Session in 1852 after giving birth to an illegitimate child – Annie’s great-grandfather, George Ferguson – which was regarded as scandalous behaviour in the Victorian era. Her maternal grandparents, William Ferguson and Dora Paton, were a gamekeeper and a dairymaid; two different sides of the coin which flicked between Balmoral and Torry.

Ultimately, there’s no definitive description which applies to Annie Lennox. As she once told the Press & Journal, she was grateful for the music tuition she received at school. But….”I had to leave Aberdeen in order to develop musically. Yet, if I hadn’t had the chance to have the musical experiences I had as a child here, I don’t think I would have gone on to be in Eurythmics in the first place.”

There’s a grand Scottish word for people such as her: thrawn. If the term is applied to a man, it’s usually done admiringly. If it’s a woman, then she must be difficult. Just don’t use these words in Annie Lennox’s company!

By: Neil Drysdale