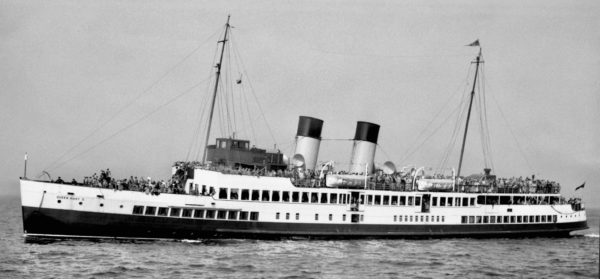

We call our ships by many names: ‘snakes of the seas’, ‘surf dragons’ and ‘fjiord elkes’. The seas they sail upon we call ‘the whale’s road’, ‘eel home’, fish’s bath’ and ‘Njord’s hall’. Many things may befall you upon the whale’s road so take care. Make offerings to the sea lord Njord before leaving land. Carve runes of protection upon your oars and your mast. Ask Thor for fair weather. Be wary of monsters for many dwell in the murk of deep sea halls. Serpents and sea trolls sink many ships so muster the power of some mighty runes before setting sail.

Seafarer’s Lore from ‘How to be a Viking’ by Art Berk.

In 1262 AD, the King of Scotland, Alexander III when scarcely more than a boy, launched a desperate bid to recover the Western and Northern Isles of Scotland from the King of Norway, Haakon IV. The Scots kings were no longer prepared to tolerate Norse occupation of any part of their kingdom. In 1196 Alexander’s grandfather, King William the Lion, had thrown the Vikings out of northern Scotland. Alexander III was one of Scotland’s better kings, said to be good and wise. He stirred up various Highland nobles such as the Earl of Ross to make war upon the island chiefs on behalf of their King. The chiefs turned to King Haakon for his military assistance to combat the Earl of Ross’s incursions in to what they considered were their lands. Haakon decided to retaliate against the Scottish king. The subsequent invasion and vicious raids by Haakon upon Loch Long and Loch Lomond were almost certainly his response to Alexander’s bold initiative to take territory back from him and his Norwegian Empire. Having sailed up Loch Long Haakon was able to take the local populace of Loch Lomond by surprise by rolling his longships over the narrow strip of land between the sea loch and the land-locked Loch Lomond, at what to us is now called Tarbert. There was much slaughter there as a consequence.

Largs

At Largs my extended family often took their evening walks along the esplanade toward the Googie Burn and the Pencil Monument, called that simply because of its shape and built to commemorate the Battle of Largs, fought near there in 1263. My father talked of a great battle having taken place. He spoke of King Alexander III, high on the Renfrewshire hills behind Largs, watching Haakon’s fleet of 120 or so longships beating a passage from the Mull of Kintyre and Lorne, toward the Isle of Bute to finally anchor off the coast of Arran. Eventually the fleet lay off the Cumbraes readying to land at Largs. He continued with the conventional story that Alexander and his army strategically lay in wait with his hidden forces at a place that came to be called Camphill lying in those hills. And went on to say that when Haakon launched his dragon ships upon the coast his Viking crews were met head on and repulsed by Alexander’s cavalry and foot soldiers in a bloody and victorious battle.

That was my father’s version of events; however some historians describe it very differently. They talk of an aging and tired King Haakon bringing his large fleet of longships in an attempt to halt what he saw as Scottish imperialism against his Western Isles Kingdom and his loyal island chiefs. He had bargained on the support of Angus, the chief of the powerful Clan Donald. But Haakon was outsmarted because Alexander held Angus’s son hostage and so Angus was unable to help. Unfortunately for Haakon, he had already delayed too long in making his way through the Western Isles towards Largs. Alexander now wasted another month of Haakon’s time in ‘negotiation’ while Haakon’s unruly men became bored, and discipline became slack. They took to raiding the Ayrshire coast for something to do to fill in their time. Some historians even suggest that Alexander, rather sneakily, delayed Haakon’s progress by sending friars to pretend to negotiate a treaty but in reality meaning to prolong him further toward the season of autumn gales. How they got aboard his ships without getting a battleaxe though their heads is not mentioned. Nevertheless, these gales are said to have played havoc with Haakon’s fleet as it lay in the Firth of Clyde and the autumn storms are said to have wrecked many of his ships before they ever got on to the coast at Largs. Haakon had dithered too long and on the fateful night of the 1st of October 1262 a great storm came in from the west and pushed his longboats toward the coast whether they liked it or not. Haakon was forced to order a difficult landing. With much of his invasion fleet already scattered some longboats got smashed on the shore and many of his men were drowned.

Significant effect upon Scottish history

Some historians would have us further believe that Haakon and his bedraggled Viking warriors, those who had survived this disaster, stumbled ashore at Largs, completely exhausted, to have to face King Alexander and his army including 1,500 armoured cavalry, charging toward them along the shoreline. In the course of a rather confused engagement Haakon’s men were defeated on both the land and the sea to ave to withdraw in disorder. The Scot’s army, then supposedly, politely withdrew to allow the weary Norwegian Vikings, short of food and supplies, never mind fighting spirit, to fall back, retreat and sail away, back by the way they had come. What is known for sure is that Haakon, no matter whether defeated soundly in battle or not, or simply a poor wee king in distress, no longer had the heart and stomach for a future confrontation. Completely disheartened by this turn of events he apparently sailed back to Norway with what remained of his fleet, stopping off on the way in Kirkwall, in the Orkneys, only to take ill, sccumb to fever and die there.

No matter what the truth is about the Battle of Largs. It had a long-term and very significant effect upon Scottish history. Within three years by the Treaty of Perth, made with Magnus, Haakon’s successor the Western Isles and the Isle of Man passed back by sale to the Scots, whilst the Northern Isles, the Orkney and Shetland Islands remained in Norwegian hands as part of the Viking empire. In 1283 King Eric of Norway, was married to King Alexander’s daughter, Margaret to put a seal on the peace treaty of twenty years before. Then tragically within a short time the popular King Alexander died at Kinghorn in Fife when riding up a cliff path in fog to join his young wife. He was found dead at the foot of a precipice. His wife, his daughter and his other children were all dead, one after another within a short time. His surviving three-year-old grand-daughter, Margaret, the Maid of Norway, became heir to the Scottish throne as her infant queen. In turn this child’s untimely death in Orkney led to a dynastic crisis which de-stabilised Scotland, destroyed the relative peace between England and Scotland and began Scotland’s exploitation by England’s Edward I and ultimately to the Wars of Independence. The Battle of Largs was therefore a very significant turning point in Scotland’s history whether it followed the battle script of my father, spoken to me on those delightful evening walks to the Pencil Monument or that based upon the research of more qualified historians regarding that fatal day in 1253.

Australian Jim Stoddart was born in a Glasgow Tenement and raised in a Glasgow Housing Scheme 1943-1965. Jim will be taking readers on a trip down memory lane, of a time and place that will never be the same again and hopes even if only a few people in the Scot’s Diaspora have a dormant folk memory awakened, then he shall be more than delighted.

Main photo: The Pencil Monument, Largs. Photo: VisitScotland.